FTC Settles with Major Ad Platform for Deceptive Location Tracking via Wi-Fi

The FTC announced a settlement today with InMobi, a major advertising platform provider, for engaging in deceptive location tracking practices. As explained below, InMobi used alternative methods to collect location data from users, even after the users had chosen not to share their location in apps via Location Services. But InMobi’s major mistake—misrepresenting the fact that they were collecting location data anyway via Wi-Fi networks—is one that many companies need to pay close attention to. There are many ways that location is collected about mobile devices and describing the options correctly can be difficult, especially if a partner’s practices are not transparent.

As the Future of Privacy Forum staff have explained in filings to the FTC and FCC as well as in a 2015 report on cross-device tracking, there are many ways that consumer devices are tracked. In this summary, we explain what exactly was happening, and how controls over various methods of location sharing are often misunderstood.

InMobi collected location information regardless of the common Location Services permission provided by users

InMobi provides a mobile advertising platform; by partnering with InMobi and integrating their software development kit (SDK), app developers can monetize their apps through targeted advertisements, and advertisers can target consumers via any apps which have integrated InMobi’s SDK.

Much of this advertising is geo-targeted—InMobi gives advertisers the ability to target ads based on the user’s precise location, as well as the patterns of locations of where the user had been over the previous two months. In iOS and Android phones, the operating system requires that an app has to ask your permission before it shares your location via Location Services, so consumers (and app developers) assumed that this geo-targeting was based on opt in consent. And in fact, InMobi told developers that geo-targeted ads were based on opt in consent. So far, so good.

The big problem—and the reason they were just penalized by the FTC—was that prior to December 2015, even when a user had declined to provide their location by selecting “no” in response to the app’s request (or turning it off manually in the phone Settings), InMobi used an alternative method to infer their location via the information collected about the Wi-Fi network to which the user was connected; and/or the Wi-Fi networks in range of the device. By compiling this information into a geo-location database (along with the more detailed information from users who had opted in to Location Services), InMobi could match Wi-Fi networks to specific locations. Despite this practice, the company told developers that geo-targeting was only available if users gave their permission via Location Services, thus opening the door to an injunction and civil penalties from the FTC for deceptive practices.

No Surprise: Many Alternative Methods for Location Targeting Exist

InMobi’s behavior was deceptive because they misrepresented their data collection—that is, they told the public and app developers that geo-targeting required opt-in consent, stating that they would respect users’ choices, and then didn’t respect those choices. However, the use of Wi-Fi itself to infer location is not new, and comes as no surprise. We have explained, in filings to the FTC and FCC, as well as in a report on cross-device tracking, that it is easier than ever to gather location data through smartphones using a variety of methods.

Of the methods by which apps can determine location, users are often most familiar with Location Services, the service controlled by the mobile operating system (OS). This is the primary way apps request location permission, and it’s usually optimal because it aggregates data from different sources—including GPS, cellular triangulation, nearby Wi-Fi signals, and Bluetooth positioning—to pinpoint the device’s location more accurately than any individual system.

But most users are not familiar with the range of other methods that can be used to determine a device’s location. These include cell tower location (cell towers broadcast unique Cell IDs, which are compiled in publicly available databases); carrier triangulation (uniquely, mobile ISPs can analyze signals from multiple surrounding cell towers); Wi-Fi networks (as explained below); beacons (small radio transmitters that broadcast one-way Bluetooth signals to apps that can receive them to infer proximity); and mobile location analytics (passive detection of devices’ Wi-Fi MAC addresses or Bluetooth addresses to determine things like airport or retail traffic).

How does an app determine location through Wi-Fi?

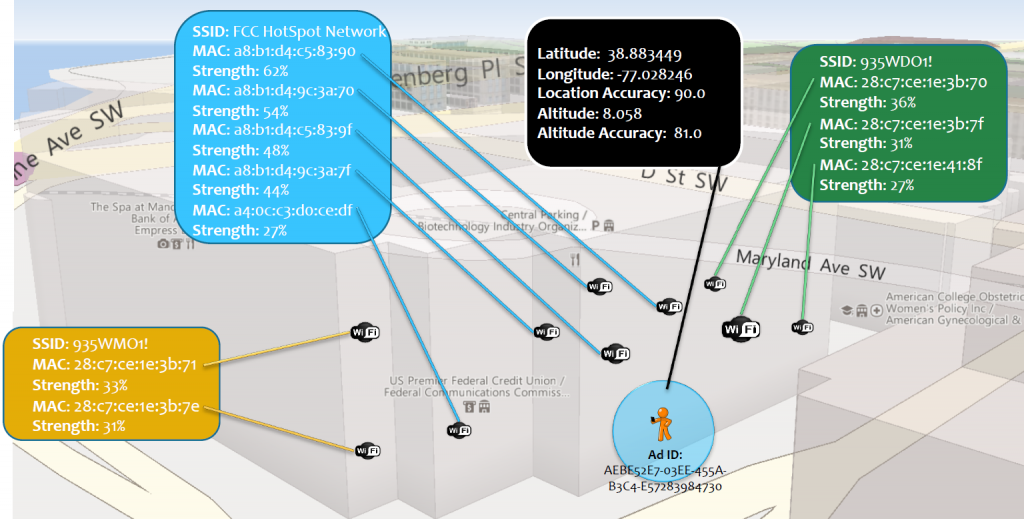

Even without access to Location Services, apps can infer geo-location through the device’s routine scanning for nearby Wi-Fi networks. Large databases exist of the unique identifiers (MAC addresses and SSID) of wireless routers and their known locations, which are continuously updated in a variety of ways, including by the mobile operating system itself (with permission during set-up). An early report in 2014 specifically documented the use by InMobi of this method of using local and previously logged Wi-Fi networks to capture location information.

Mobile devices can infer geo-location by scanning for the MAC addresses and SSIDs of nearby publicly broadcasted Wi-Fi access points.

Deception via Misrepresentation to App Developers

It’s particularly interesting to note that in addition to making certain public statements in their own marketing campaigns, InMobi also misrepresented their geo-targeting practices in their statements to app developers. The FTC’s Complaint focuses on the fact that the InMobi SDK integration guides for Android and iOS developers contained inaccurate statements. As a result, the FTC states:

“. . . numerous application developers that have integrated InMobi SDK have represented to consumers in their privacy policies that consumers have the ability to control the collection and use of location information through their applications, including through the device location settings. These application developers had no reason to know that Defendant tracked the consumer’s location and served geo-targeted ads regardless of the consumer’s location settings.” FTC Complaint para. 37 (emphases added).

This focus is especially interesting in light of the fact that most FTC enforcement actions for deceptive business practices focus on misrepresentations in a company’s own privacy policy.

Going Forward

Apps can provide great value to consumers by using location for a wide range of services and geo-targeted ads can often provide useful relevant information. But app developers need to understand and demand transparency from their partners so that they can be accurate and honest with their consumers.

Read the FTC’s Complaint and Settlement here.

Read FPF’s Cross-Device Tracking report here.

For media inquiries, contact:

Melanie Bates