Diverging fining policies of European DPAs: is there room for coherent enforcement of the GDPR?

The European Union’s (EU) General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) puts forward a non-exhaustive list of criteria in Article 83 that Data Protection Authorities (DPAs) need to consider when deciding whether to impose administrative fines and in determining their amount in specific cases. Notoriously, the ceiling for administrative fines put forward by the GDPR is high – up to 20M EUR or 4% of a company’s worldwide annual turnover for breaching specific rules (e.g. the rights of the data subject), and up to 10M or 2% of the same turnover for breaching the rest of the provisions (e.g. data security requirements), leaving ample room to calibrate the fines to the facts of a case.

While it was expected that independent DPAs would give the criteria different weight in their enforcement proceedings, depending on their own legal and cultural context, the past four years of enforcement experience have shown that fining policies and practices vary considerably among EU DPAs.

Some DPAs decided to formulate fining policies and publish them, while others merely built their own body of case-law and created practice around how these criteria are applied without formalizing such policies. The DPA of the German State of Bavaria was one of the first to publish non-binding guidance on the matter: in September 2016, it revealed it would devote particular attention to previous data protection infringements and the degree of collaboration the investigated parties offer during the proceedings.

To avoid having DPAs taking diverging approaches to setting fines under the new framework, the old Article 29 Working Party published its 2018 guidelines early on, before the GDPR became applicable, which were later endorsed by the European Data Protection Board (EDPB). They quote directly Recital 11 of the GDPR, stating that “it should be avoided that different corrective measures are chosen by the [DPAs] in similar cases.” Indeed, administrative fines are only one among several corrective measures in DPAs’ toolbox, which also includes the issuance of reprimands, compliance orders, suspension of data flows to recipients in third countries, and even temporary or definitive limitations or bans on data processing (Article 58(2) GDPR). Thus, the EDPB further clarified that fines should not be seen as the last resort available to DPAs and that it is not always necessary to supplement fines with other corrective measures.

While the EDPB guidelines provided inspiration for a few fining policies adopted by national DPAs, the authorities do not shy away from taking innovative approaches to standardize their fining procedures, as will be shown below. Other regulators (such as the Irish and the Belgian DPAs) have announced they plan to provide clarity and predictability to organizations about their sanctioning standards by publishing their own methodologies in this regard. Nonetheless, it is possible that some DPAs are waiting for the approval of upcoming EDPB guidance on the calculation of administrative fines to adopt their stance. As the publication is bound to happen in the coming days, FPF’s new piece outlines the similarities and differences between the few national fining policies published by European DPAs since 2018. This analysis and the differences it outlines show why it was necessary for the EDPB to adopt new guidance on this matter.

This blog post provides an overview of the only comprehensive fining methodologies that were published so far by EU DPAs (specifically, by the Dutch, Danish, and Latvian DPAs), as well as the relevant draft Statutory guidance issued by the UK DPA (ICO) in 2020. Therefore, this analysis will also show how the approach of the ICO in this matter will likely continue to differ from that of the EDPB and EU DPAs. It is divided into two sections that take a deep dive into (i) how those DPAs propose to apply the criteria set out in Article 83(1) to (3) GDPR in practice – highlighting where they diverge from the 2018 EDPB guidelines – and (ii) how they propose to standardize the amounts of the fines imposed against controllers or processors in their jurisdictions.

1. Balancing the same criteria with different scales

According to Article 83(2) GDPR, all DPAs need to consider the same non-exhaustive list of criteria when deciding whether to sanction controllers or processors with administrative fines for breaches of the GDPR, instead of or in addition to other corrective measures. These criteria also guide DPAs’ decisions on the determination of the amounts of the fines they impose in individual cases.

However, the analysis of the published DPA fining methodologies shows that different regulators attribute varying degrees of importance to these factors in both those exercises, sometimes deviating from the EDPB guidelines.

The Dutch DPA guidance does not generally provide indications as to how the regulator proposes to weigh in such factors nor the financial circumstances of the infringer in specific cases.

Article 83(2)(a) GDPR: Nature, gravity and duration of the infringement, including the nature, scope or purpose of the processing, the number of data subjects affected and the damage suffered by them

On this criteria, the EDPB guidelines from 2018 state that, in case of “minor infringements” or infringements carried out by natural person controllers, DPAs may generally opt for reprimands instead of fines as suitable corrective measures. The guidelines add that damages suffered by data subjects and the long duration of infringements should count as aggravating circumstances in DPAs’ assessments regarding the need for imposing and increasing the value of fines.

The ] recent (September 2021) Danish DPA (Datatilsynet) guidance on the determination of fines for natural persons seems to contradict the EDPB approach that fines may be dismissed by DPAs in these cases. The Datatilsynet guidance complements its January 2021 guidelines on the determination of fines for legal persons and proposes a table of standardized fines for natural person controllers who commit certain GDPR breaches (such as publishing others’ sensitive personal data in social media outlets). Regarding this criterion, the guidelines applicable to the sanctioning of legal persons establish that the DPA must have due regard to several factors, including whether the processing purpose is purely profit-seeking (e.g. marketing) or benevolent (e.g. calculating an early retirement pension), and whether data subjects’ rights have been breached (i.e., the concept of “damage” should be interpreted broadly).

Concerning the latter criterion mentioned by the Danish DPA, the ICO’s Regulatory Action Policy illustrates that the UK regulator takes a different approach. The Policy states that, for “damages” to count as an aggravating circumstance, a degree of damage or harm (which may include distress and/or embarrassment) must have been suffered by data subjects.

Lastly, the Latvian DPA’s guidance stresses that the criteria listed under Article 83(2)(a) GDPR may carry more weight than others when it comes to determining fines. As an example, the Latvian watchdog states that the duration of the breach and the number of data subjects affected is generally more important than the financial benefits obtained by the controller. This is also reflected in the table of points that the DPA shall use to determine the amounts of fines in individual cases, which is explored below.

Article 83(2)(b) GDPR: the intentional or negligent character of the infringement

Again, DPAs consider this factor in different ways and at different moments of the process of determining a fine. Nonetheless, they seem to agree that the higher the degree of imputation (negligence -> gross negligence -> intent), the higher the fine should be. It also surfaces from EDPB guidance that controllers and processors cannot justify breaches of data protection law by claiming a shortage of resources.

When assessing the infringer’s degree of culpability, the ICO takes into account the technical and organizational measures that had been implemented by the controller of processor, notably whether a lack of appropriate measures may reveal gross negligence. Additionally, the UK regulator will consider more severely cases of wilful action or inaction of the infringer with a view to obtain personal or financial gains.

The EDPB and the Danish DPA, on the other hand, are quite aligned when it comes to giving examples of negligent and intentional infringements, including:

- Negligent breaches: non-compliance with existing policies, human error, lack of control of published information, lack of timely technical updates; and

- Intentional breaches: decisions taken by the company’s Board against a DPO’s correct advice/despite existing internal policies, purposely amending personal data to make it inaccurate, and selling personal data without consent.

Of note, after the UK left the EU in 2020 the ICO is not bound anymore by EDPB guidance. Therefore, this may be one area where divergence in approaches to implement the GDPR and the UK GDPR will remain.

Article 83(2)(c) GDPR: any action taken by the controller or processor to mitigate the damage suffered by data subjects

The EDPB stresses that DPAs should look into whether the infringer did everything it could to reduce the consequences of a breach for data subjects. In that case – and also where the infringer admits its infringements and commits to limit its impacts -, this should count as a mitigating factor when determining the fine. As for national DPAs:

- For the Datatilsynet, collecting evidence that unauthorized recipients of personal data have deleted the information is an example of relevant mitigating action.

- The Latvian DPA highlights that it shall only consider damage control actions taken by the controller as a mitigating factor where such actions have been taken in due time (i.e. if they were actually effective).

- Failure to adopt any such measures could also be considered as an aggravating circumstance by the ICO.

Article 83(2)(d) GDPR: the degree of responsibility of the controller or processor taking into account technical and organizational measures implemented by them

Once again, the EDPB and the Danish DPA seem to be in sync regarding the interpretation and the application of this criterion. In essence, DPAs must ask themselves whether the infringer has implemented the protective measures that it was expected to, considering the nature, purposes, and extent of the processing, but also current best practices (industry standards and codes of conduct). If so, this should be taken as a mitigating circumstance in the fine’s calculation.

Article 83(2)(e) GDPR: any relevant previous infringements by the controller or processor

On this criterion, there is some degree of divergence between approaches of the DPAs. The EDPB has tried to set the baseline by recommending DPAs focus on whether the entity committed the same infringement earlier or different infringements in the same manner, whereas prior breaches which are different in nature may still be included in the assessment.

The Danish DPA commits to a deeper analysis under this criterion, stating that it shall weigh breach findings made by other DPAs against the infringer, as well the latter’s breaches of the data protection framework which was in place prior to the GDPR. However, it also stresses that:

- breaches of the GDPR should be considered more relevant than breaches of the previous law;

- the longer the time that has elapsed between a previous infringement and the current one, the less weight it must have in determining the fine; and that

- infringements that occurred more than 10 years prior to the infringement at stake become irrelevant.

In a rare indication of the degree of importance it attributes to specific factors listed under Article 83(2) GDPR, the Dutch DPA reveals that, in case the infringer breaches the same provision that it previously had, the DPA should increase the standard fine by 50% (see the DPAs’ methodology below).

The ICO mentions that it is more likely to impose a higher fine in case of a failure by the infringer to rectify a problem which was previously identified by the regulator, or to follow previous ICO recommendations. Lastly, for the Latvia DPA, the existence of past breaches counts as an aggravating circumstance when determining the fine, whereas a lack of past offenses does not put the infringer in a more favorable position.

Article 83(2)(f) GDPR: the degree of cooperation with the supervisory authority, in order to remedy the infringement and mitigate the possible adverse effects of the infringement

Under this criterion, the EDPB guidelines invite DPAs to consider whether the entity responded in a particular manner (that was not strictly required by law) to their requests during the investigation phase, in a manner that has significantly limited the impact on individuals’ rights. The Danish DPA’s take on the matter is again very aligned with the EDPB, adding that an admission or confession of the infringement by the infringer should count as a mitigating circumstance.

It should be noted that a refusal to cooperate can, in itself, constitute a breach of the GDPR, as it is an obligation applicable to controllers and processors alike, under Article 31. In this regard, the Danish DPA considers such failure to cooperate as one of the less serious infringements that fall under Article 83(4) GDPR, while the Dutch DPA frames it as one of the gravest. In Chapter 2 below, we analyze how this framing translates into standardized basic amounts for each of both DPAs’ fines.

Article 83(2)(g) GDPR: the categories of personal data affected by the infringement

According to the EDPB, DPAs should carefully look into whether the GDPR infringement at stake affected special categories of data or other particularly sensitive data that could cause damage or distress to individuals. Such sensitive data could include data subjects’ social conditions and personal identification numbers, as stated by the Danish DPA. For the Datatilsynet and the Dutch DPA, unlawful processing of special categories of data counts as one of the gravest infringements under Article 83(5) GDPR, which may lead the former to maximize the basic amount of the fine in a given case.

For the EDPB, it is also important that DPAs understand the format in which the data was compromised: was it identified, identifiable, or subject to technical protections (such as encryption or pseudonymisation)? The ICO intends to issue higher fines in cases involving a high degree of privacy intrusion. With a different focus, the Latvian DPA highlights that a significant number of affected data categories can justify imposing a higher fine, in particular when it comes to children’s data.

Article 83(2)(h) GDPR: the manner in which the infringement became known to the supervisory authority, in particular whether, and if so to what extent, the controller or processor notified the infringement

In this context, DPAs should in principle more critically assess infringements of which they become aware through means other than a notification from the infringer. According to the EDPB, the fact that a breach is uncovered via an investigation, a complaint, an article in the press or an anonymous tip should not aggravate the fine. However, the fact that an infringer actively tries to conceal a breach can increase the amount of the fine set by the DPA in Denmark, according to the latter’s policy.

On the other hand, a notification delivered by the infringer to the DPA to make it aware of an infringement may count as a mitigating circumstance, as stressed by the EDPB. The Latvian DPA’s list of criteria mentions that the more timely and encompassing the notification of the infringer is, the more it will help decrease the amount of the fine.

Article 83(2)(i) GDPR: compliance with previously-ordered measures against the controller or processor concerned with regard to the same subject-matter

The Danish DPA has stressed that it shall assess infringements more severely where it has previously warned the perpetrator that its conduct constituted a violation of data protection law or ordered it to align its practices with legal standards. The Latvian DPA may issue an aggravated fine in case the infringer refused to correct its data processing pursuant to a DPA order.

Article 83(2)(j) GDPR: adherence to approved codes of conduct pursuant to Article 40 or approved certification mechanisms pursuant to Article 42

Both the Danish and the Latvian DPAs mention that adherence to those frameworks could demonstrate the willingness of the infringer to comply with data protection law. In some cases, adherence to codes of conduct or certification mechanisms may even exclude the need of imposing an administrative fine altogether: the EDPB stresses that DPAs may find that enforcement or action taken by monitoring or certification bodies in certain cases is effective, proportionate, and dissuasive enough.

Lastly, it should be noted that DPAs have the power to sanction codes of conduct’s monitoring bodies for a failure to properly monitor and enforce compliance with such codes, under Article 83(4) GDPR. In this respect, the analyzed fining policies show that the Danish DPA views such failure as one of the less serious breaches listed under the provision, while the Dutch DPA frames it as one of the gravest.

Article 83(2)(k) GDPR: any other aggravating or mitigating factor applicable to the circumstances of the case, such as financial benefits gained, or losses avoided, directly or indirectly, from the infringement

The wording of this criterion opens the door for DPAs to consider any other factors in their fine determination exercise, also hinting that the criteria set out under Article 83(2) are not exhaustive. As an example of how to consider the criterion in a specific case, the EDPB guidelines state that the fact that the infringer profited from the conduct “may constitute a strong indication that a fine should be imposed.” The ICO also commits to focus on removing any financial gains obtained from data protection infringements.

In Denmark, this may entail confiscating the profits which were illegally obtained as a result of the data protection breach, or the inclusion of such profits in the amount of the imposed fine. However, the Danish DPA’s policy states that it may be challenging and quite resource-intensive to determine such profits, regardless of the chosen avenue.

Fines must be effective, proportionate and dissuasive: How do DPAs make sure they are as such?

Article 83(1) GDPR requires DPAs to ensure that administrative fines are effective, proportionate, and dissuasive in each individual case. The EDPB specifies that, although this exercise requires a case-by-case assessment, a consistent approach should eventually emerge from DPA enforcement practice and case law.

Regardless of the fact that this criterion shows up first in the text of the GDPR, both the UK, Latvian and Danish DPAs prefer to check their determined fine amounts against those factors only at the end of the process. For example, the Datatilsynet states that a fine that would jeopardize the finances of the infringer and leave it close to bankruptcy could be considered effective and dissuasive, but likely not proportionate. In such circumstances, the DPA may consider whether to impose more moderate payment terms (e.g., deferral of payment) or even to reduce the amount of the fine.

The ICO also considers the infringer’s financial means when deciding on the fine: if the determined fine would cause financial hardship for the infringer, the regulator may reduce the fine. Additionally, the ICO is bound by national law to assess the fine’s broader economic impact, as it must consider the desirability of promoting economic growth. Thus, before issuing a fine and when deciding on its amount, it will consider its economic impact on the wider sector where the infringer is positioned.

With regards to the fine’s effectiveness, proportionality, and dissuasiveness, the Latvian DPA’s list of criteria mentions that the watchdog will have due regard to elements such as the infringer’s profits, number of employees, special status (e.g. as a social enterprise), and its wider role in society.

Article 83(3) GDPR as the fine’s ceiling: Towards a common interpretation?

The provision reads that “if a controller or processor intentionally or negligently, for the same or linked processing operations, infringes several provisions [of the GDPR], the total amount of the administrative fine shall not exceed the amount specified for the gravest infringement”. Seeking to resolve any possible interpretation issues, the EDPB’s guidelines stress that “The occurrence of several different infringements committed together in any particular single case means that the DPA is able to apply the administrative fines at a level which is effective, proportionate and dissuasive within the limit of the gravest infringement.”

Coming up with further clarification, the Danish DPA’s policy states that Article 83(3)’s ceiling should cover both situations where controllers breach different GDPR provisions with a single act, as well as others where controllers breach a single provision multiple times with a single action (e.g. sending unsolicited marketing emails to multiple recipients once). The Latvian DPA adds that, in those cases, all breaches must be considered together and the corresponding administrative fine should be calculated considering the gravest infringement.

This seems to be different from limiting DPAs to sanction infringers only for the gravest among several infringements they have committed, as the EDPB has recently clarified in its binding decision 1/2021 under Article 65(1) GDPR on the Irish DPC’s draft decision against Whatsapp Ireland. In that context, the EDPB stated that “Although the fine itself may not exceed the legal maximum of the highest fining tier, the infringer shall still be explicitly found guilty of having infringed several provisions and these infringements have to be taken into account when assessing the amount of the final fine that is to be imposed” (para. 326).

2. Making fines predictable: A road to harmonizing enforcement standards?

All the European DPAs that have published fining policies in the last two years have tried to pave the way towards a standardization of the assessments that lead to the determination of an administrative fine. This is well demonstrated by the formulas and tables that DPAs have created to guide such a determination process. But are the DPAs’ approaches consistent, in a way that may lead to harmonized enforcement of data protection rules in Europe, so as to avoid forum shopping?

Dutch DPA (AP)

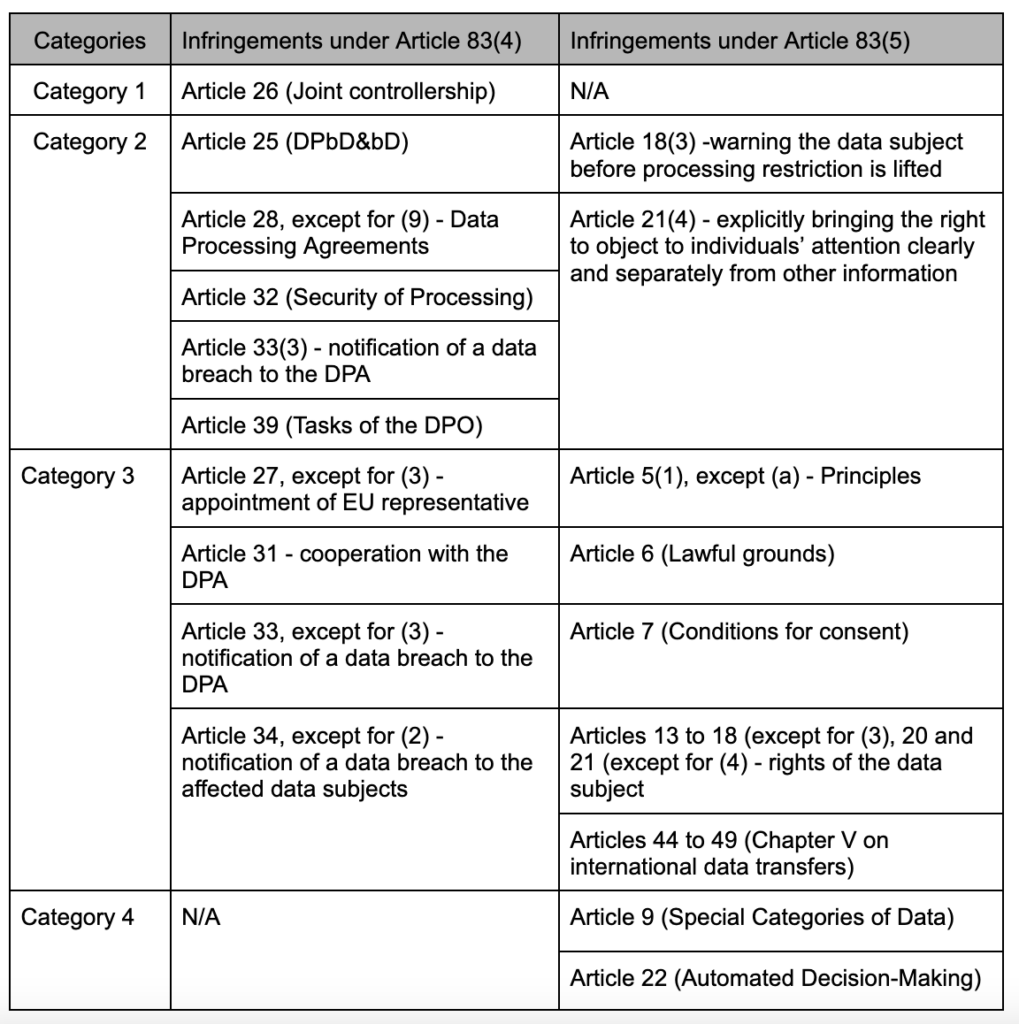

As the first of its kind among EU DPAs’ guidelines, the Dutch DPA’s fining policy is groundbreaking in the way it proposes that the AP should determine the fines it decides to impose for GDPR infringements. It starts by splitting infringements into 4 different categories in accordance with their seriousness, as illustrated below with some examples:

Then, it uses the below table to determine the standard (basic) fine that corresponds to the infringement(s) at stake:

| Category 1 | Fine range: 0€ to 200.000€ | Basic fine: 100.000€ |

| Category 2 | Fine range: 120.000€ to 500.000€ | Basic fine: 310.000€ |

| Category 3 | Fine range: 300.000€ to 750.000€ | Basic fine: 525.000€ |

| Category 4 | Fine range: 450.000€ to 1.000.000€ | Basic fine: 725.000€ |

To determine the fine’s final amount, the AP uses the basic fine as a starting point and may move it upwards or downwards until the top or bottom of the fine bandwidth for the respective category of infringement. In doing this, the DPA must assess the factors listed under Article 83(2) GDPR, as well as the financial circumstances of the infringer.

However, the DPA may decide to go above or below the bandwidth if it finds that the fine in the default bandwidth would not be appropriate in the specific case. It can then go up to the legal limit of the fine for the respective infringement (10/20M EUR or 2/4% of annual turnover). In case or reduced financial capacity of the infringer, the DPA can choose to go below the immediately lower fine bandwidth when determining the fine.

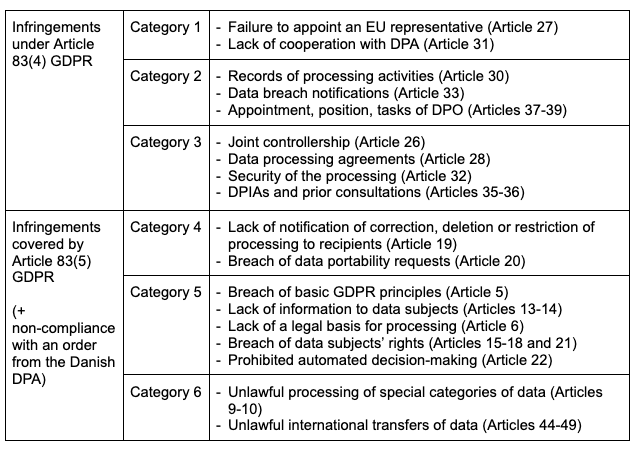

Danish DPA (Datatilsynet)

First of all, it is important to note that the Danish DPA is one of only two EU DPAs (together with the Estonian DPA) that does not have the legal attributions under its national law to issue administrative fines. It needs to report an infringement of data protection law to the police, along with a determined fine recommendation, so that the infringer is investigated and prosecuted and that a court may ultimately sentence the infringer to pay the fine.

For guiding prosecutors and courts in this regard – which shall also consider the Danish Public Prosecutor’s guide on criminal liability for legal persons -, the Danish DPA thus favors a “standardization” of the levels of fines for specified breaches of data protection law. This should be complemented by a case-by-case assessment, considering the criteria under Article 83(1) to (3) GDPR and the infringer’s ability to pay.

With regards to fines issued against legal persons, the Datatilsynet advises prosecutors to start with determining the fine’s baseline amount, considering the provision of the GDPR which was infringed: it thus separates between infringements leading to 10M EUR/2% of annual turnover fines (first three categories in the table below) and others leading to 20M EUR/4% of annual turnover fines (last three), which we illustrate with some examples:

This division into 6 categories was made by the Danish DPA according to its own assessment of the GDPR provisions at stake, notably of their importance, place in the Regulation and their underlying protection objectives. Categories 1 and 4 are the less serious infringements within their respective provisions. Categories 2 and 5 are more serious infringements and Categories 3 and 6 are the most serious ones.

The “dynamic ceiling” of the fine (2% or 4% of annual turnover) only applies to companies with an annual global (net) turnover – as defined in Article 2(5) of Directive 2013/34/EU – exceeding 3.75M DKK (around 504M EUR). Once the maximum fine in the individual case has been determined, the standard basic amount of the fine may be set as follows:

- 5% of the maximum amount for infringements falling under Categories 1 and 4

- 10% of the maximum amount for infringements falling under Categories 2 and 5

- 20% of the maximum amount for infringements falling under Categories 3 and 6

The basic amount must also consider the size of the breaching company: it should be adjusted in case of SMEs (according to the EU definition). Thus, for the latter, the basic amount of the fine should be adjusted as follows:

- Micro-enterprises: down to 0.4% of the standard basic amount

- Small enterprises: down to 2% of the standard basic amount

- Medium-size enterprises: down to 10% of the standard basic amount

The infringer’s market share should also be taken into account (e.g., an infringement by a company with a low revenue but a significant market share may affect a large number of data subjects).

Once the basic amount has been determined, the Danish DPA recommends the prosecutor to adjust the fine to the criteria set out in Article 83(1) to (3) GDPR – in the manner we have outlined before – and to the infringer’s ability to pay (should the latter so request it).

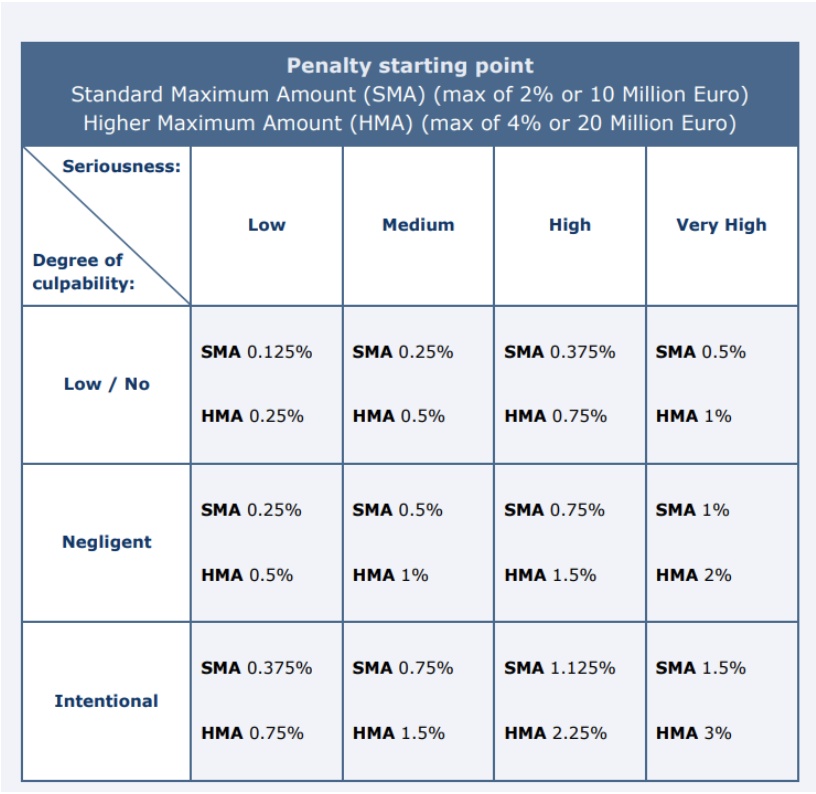

UK DPA (ICO)

The UK’s DPA also proposes to standardize the sums of administrative fines with its own formula and table. Those serve as the basis for calculating fines included in the ICO’s Penalty Notices, but also for the regulator’s preliminary notices of intent (NOI). Through the NOI, the ICO warns the infringer that it intends to issue an administrative fine, laying out the circumstances of the established breaches, the ICO’s investigation findings and the proposed level of penalty, along with its respective rationale. The infringer is allowed to make representations within 21 calendar days of receipt of the NOI, following which the ICO decides whether or not to issue a Penalty Notice.

In its draft Statutory Guidance on Regulatory Action, the ICO discloses that the process of determining the amount of a fine is a multi-step one, which starts with assessing some of the criteria set out in Article 83(2) GDPR – including the infringer’s degree of culpability and the breach’s seriousness -, as well as the infringer’s turnover after review of its accounts. Then, the ICO determines the fine’s starting point as follows:

After that, the ICO considers aggravating and mitigating factors listed under Article 83(2) GDPR to adjust the amount of the fine upwards or downwards within the previously-defined fine band. It then assesses the amount of the fine against the infringer’s financial means, the economic impact of the sanction, and the criteria of effectiveness, proportionality, and dissuasiveness. Lastly, the ICO commits to reduce the amount of the fine in 20% if it is paid within 28 days unless the infringer decides to judicially appeal the fine.

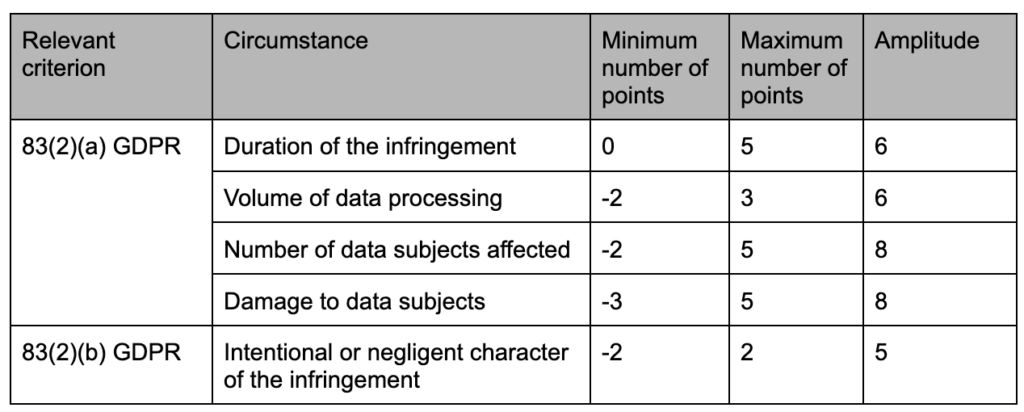

Latvian DPA (DVI)

The Latvian DPA’s process for determining the amounts of administrative fines seems to be the most complex, namely because it outlines in a very detailed fashion how the DPA should weigh each of the factors listed under Article 83(2) GDPR in specific cases.

According to the list of criteria published by the DVI in 2021, the DPA starts by determining the infringer’s relevant turnover or income: for individuals, this is the average salary in the country, multiplied by 12; for companies, this is the annual turnover, divided by 365.

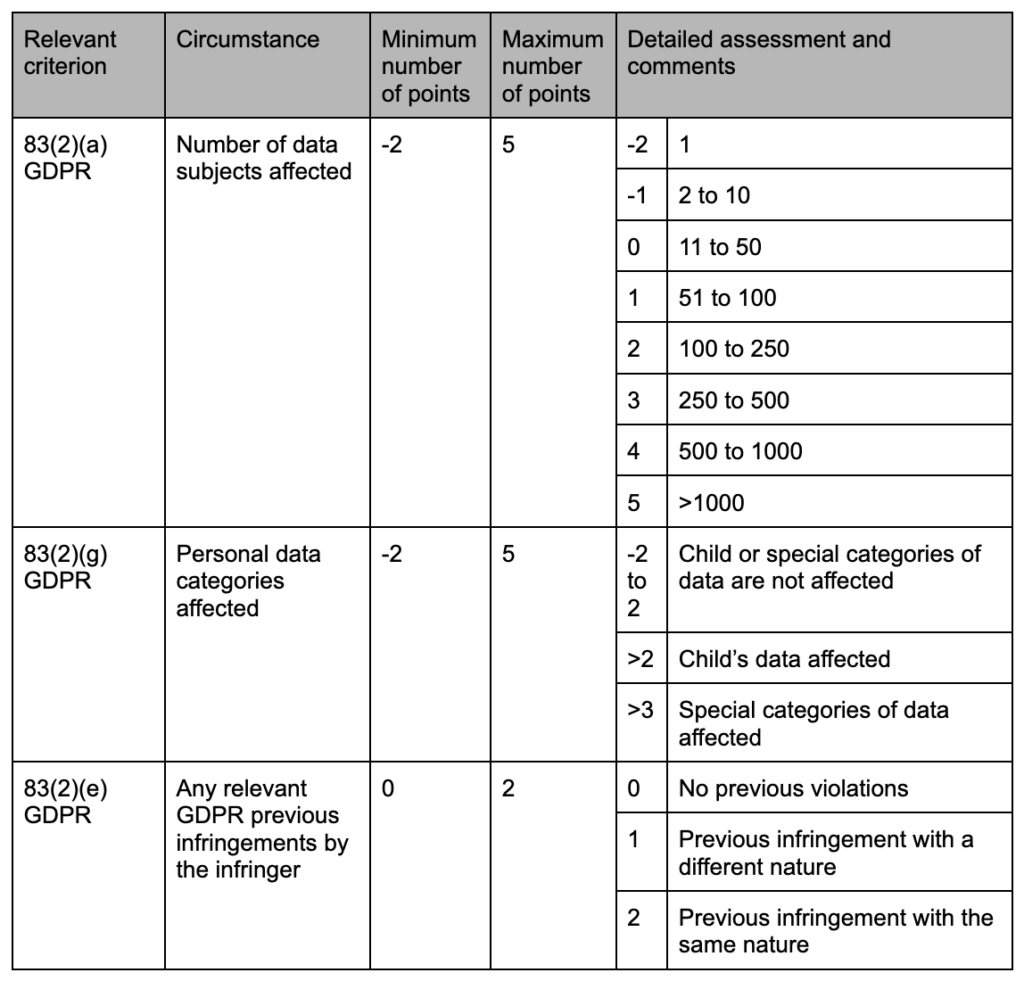

Then, the DPA selects the appropriate multiplier, which it will later apply to such turnover or income to obtain the basic amount of the fine. This serves to reflect the gravity of the infringement (low, average, high, very high). To determine the multiplier, the DPA will consider the criteria listed under Article 83(2)(a) to (j), as well as aggravating and mitigating circumstances under Latvian law. This is done in a standardized fashion, by resorting to a table, of which we provide some excerpts below:

With regards to some criteria, the DVI prefers to detail with added precision how it will apply its points attribution system, as the excerpt below demonstrates:

These tables illustrate how, for the Latvian DPA, not all criteria are inherently equally important when assessing data protection breaches, as each criterion must be given an appropriate weight. Such tables provide clarity on the way the criteria are weighed in by the DPA in cases of GDPR infringements.

Then, the DVI multiplies the relevant infringing company’s daily turnover or the individual’s annual income by a multiplier to obtain the basic amount of the administrative fine. To determine such a multiplier, the DPA considers whether there was a procedural or material breach of the GDPR, i.e., one that is covered by Article 83(4) or (5), respectively. In this regard, it uses different tables to determine the multipliers for procedural and material infringements. In case more than one procedural or material breach occurred, the DVI limits the amount of the fine in line with Article 83(3) GDPR.

The sum obtained after this calculation is then checked by the DPA against the criteria laid out in Article 83(1) GDPR and the fine ceilings set out in Article 83(4) or (5) – depending on the nature of the infringement – to reach a final amount for the fine.

A Comparative Analysis of Methodologies for Fine Calculation

As we have seen, DPAs who have published their policies with regards to administrative fines under the GDPR diverge substantially on a number of matters. These range from the importance they attribute to given GDPR infringements, to the weight they give to certain criteria that the GDPR prescribes for the determination of fines, under Article 83.

Crucially, the standard fine amounts that DPAs have published in their policies, considering the nature of the infringement at stake and the contribution of the elements listed under Article 83(2) GDPR, also have noteworthy differences:

- The Dutch DPA’s standard fine for the most serious infringements (e.g., unlawful automated decision-making) is set at 725.000 EUR;

- The Danish DPA establishes a standard fine ceiling for the most serious infringements of 20% of the maximum fine. For companies with an annual global turnover below 504M EUR, this amounts to 4M EUR;

- For intentional infringements falling under Article 83(5) GDPR and having a very high degree of seriousness, the ICO establishes that the basic amount of the fine should correspond to 3% of the maximum value defined by law. For companies with an annual global turnover below 504M EUR, this amounts to 600.000 EUR;

- Under the Latvian DPA fining framework, a company with a 504M EUR annual turnover could be bound to pay a maximum standard fine of 17.9M EUR for a “material” GDPR infringement (i.e., one that falls under Article 83(5) GDPR).

However, it is clear that this apparent gap between the DPAs’ standard fines can be closed on a case-by-case basis through consideration of additional factors when determining the final amount of administrative fines. Such elements include the infringer’s ability to pay, financial situation, annual turnover, status, societal role, and any detected recidivism.

There may be questions around the extent to which DPAs, in practice, substantially deviate from the fine bandwidths that their fining policies establish to make their fines effective, proportionate, and dissuasive. Those could only be answered through benchmarking each of the DPA’s sanctioning history under the GDPR. This is not the goal of the blogpost, which rather focuses on comparing how DPAs plan to structure their approach to fining in individual cases.

While we could not detect significant alignment in such approaches – despite the common criteria laid down in Article 83 GDPR -, it is possible that the upcoming EDPB guidance on the calculation of administrative fines could lay the ground for more harmonized sanctioning practices in the EU.

Further reading:

- FPF Report: “Insights into the future of data protection enforcement: Regulatory strategies of European Data Protection Authorities for 2021-2022”

- EDPS upcoming conference: “The Future of Data Protection: Effective Enforcement in the Digital World”

- Access Now’s 2021 Report: “Three Years Under the GDPR: An implementation progress report”