Regulating the Online Advertising Market: Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow

Today, the Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation held a hearing to examine the broad policy issues facing the Federal Communications Commission (FCC). Commissioners Pai, Clyburn, and O’Rielly outlined their priorities for the FCC, and answered questions about their proposed plans—including for the future of net neutrality and privacy of data collected online.

As we have written previously, the online advertising ecosystem is complex. In considering the role the FCC should play in regulating broadband providers, it is important to understand the history of online advertising, the current realities of an inter-connected system, and the emerging technologies that are allowing for increasingly more detailed audience profiles. In the absence of comprehensive federal privacy legislation, it will be critical in years ahead to understand the nuances of the data landscape.

Early Days of Cookie-Based Tracking and the DoubleClick-Abacus Debate

On June 4, 1999, internet advertising network DoubleClick announced that it had agreed to acquire Abacus, a major data broker, in order to link its own cookie-based web surfing data with the data broker’s information about consumer catalogue purchases. At the time, cookies were the primary mechanism for online tracking, and privacy concerns focused on how to regulate cookie-based tracking, especially when used by third party ad networks who were considered invisible to the average user. Other players, such as AOL, Yahoo, AltaVista, and Lycos were less of a concern to regulators because consumers had a direct relationship with these entities and were assumed to understand that data was being exchanged.

In response to these concerns, industry created self-regulatory regimes, including the principles and commitments outlined in the Network Advertising Initiative (NAI). Following this debate, concerns arose in the 2000’s about “adware,” or advertising “spyware,” the free programs that many consumers downloaded, unaware that the cost of the free download was ad tracking and often pop-ups. Standards and remedies arose to address this new technology, including as a result of efforts by the Anti-Spyware Coalition to advocate for practical ways to address the issues.

By the end of the 2000’s, attention shifted to major search engines, social networks, and commerce platforms. Unlike ad networks, these companies were viewed to have direct relationships with consumers through which they could explain their practices, but the breadth and scale made them the focus of much of the privacy debates in the US and globally.

Enter Apps and the Internet of Things

After the introduction of smartphones in the late 2000’s, along came a new system of mobile apps, which have become a primary alternative for consumers to access online content and services. Unlike traditional web browsing, apps do not support cookies, and their standards and permissions are enforced by the operating systems (Apple’s iOS and Google’s Android). This framework raises different privacy concerns, as developers are in some ways more limited in their possibilities for data collection, but in other ways able to collect more granular data from the smartphone’s large array of sensors.

Today, discussion has turned to the Internet of Things, as companies seek to track users across computers, tablets, phones, Smart TVs, and a range of other connected devices entering the market—including personal assistants, wearable devices, fitness trackers, refrigerators, thermostats, and security cameras. These devices, often inter-connected to comprise a “Smart Home” of automated and responsive systems, present new privacy challenges, as many policymakers seek to understand how and when they may be used to create advertising audience profiles.

Cross-Device Marketing and Emerging Proximity Technology

The drive to succeed in the online advertising market is intense and competitive. Consumers today frequently prefer and are accustomed to free online content, making it difficult to launch online businesses supported only by subscription fees. Advertising sets the terms for companies large and small, including news publishers, social networks, search engines, apps, and video streaming services. Even companies that are able to charge fees often depend on ads for some portion of their revenue.

Although consumers today have access to an expanding variety of new tools, devices, and platforms, this fragmenting of the consumer audience across platforms has been distressing to advertisers. In the past, a brand could advertise on leading TV networks and feel confident in reaching its intended audiences. Today those same audiences are accessing content across a variety of platforms, including in web browsers, mobile browsers, and apps, and across a variety of devices, including computers, smartphones, tablets, and Smart TVs. To re-link that audience, advertisers have pressed companies to connect the identities of consumers across devices and platforms.

In addition to the strong incentives to link consumers across devices and platforms, the scope and the scale of data being appended from a wide range of sources—both online and offline—is growing. As we described in our cross-device report, Oracle’s BlueKai has linked more than 80 sources of data to online IDs that can be used to target consumers based on specific audience profiles or purchasing intents—e.g. “Back to School Shopper” or “Graduation Gift Buyer.” Because targeted ads sell for many times the price of untargeted ads, Oracle’s competitors are not far behind.

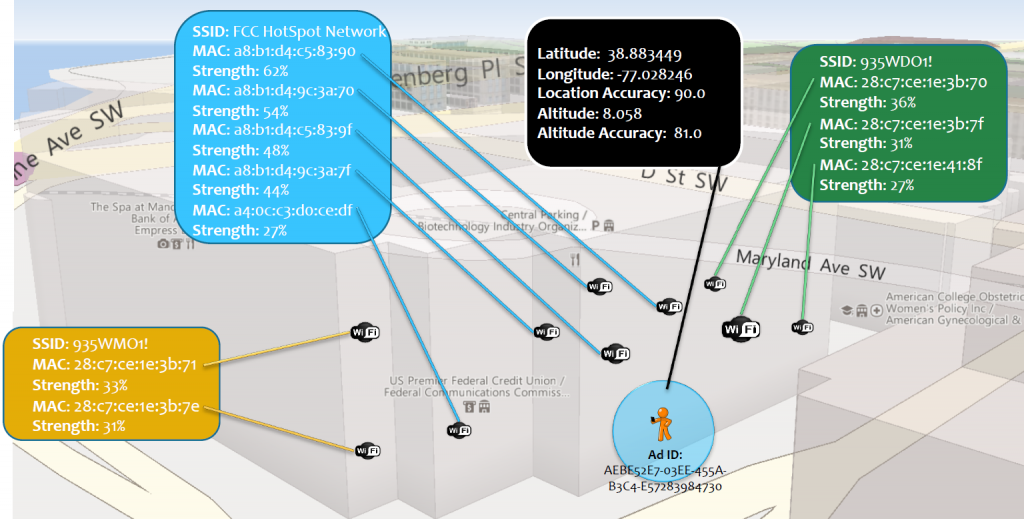

The technology continues to advance. Today, the newest data being added to consumer profiles is proximity data, or information about the places or things that can be detected as being in close proximity to a consumer. Proximity data is distinguishable from geo-location data, which has long been integrated into user profiles or available for location-based targeting. Although proximity data can sometimes be used to infer a user’s location—such as through beacons—it can also be used to detect nearby connected devices and allow for inferences based on the presence of those devices.

For example, app developers can design apps to detect nearby devices equipped with Bluetooth or Wi-Fi. When these devices are on, they broadcast SSIDs, or network names to allow users to connect with them, and MAC addresses, or unique manufacturer-assigned identifiers. MAC addresses are assigned to manufacturers by the IEEE in dedicated ranges, and as a result often correspond in predictable ways with particular types of devices. For example, if a consumer’s app detects a nearby MAC address starting with 000C8A (a range assigned to Bose), this indicates that the consumer is near to, and therefore likely owns, a Bluetooth-enabled Bose speaker. Detection of a nearby MAC address starting with 1800DB (assigned to Fitbit, Inc.) indicates the consumer probably wears a Fitbit and may be interested in health and fitness. 00199D or 006B9E? Different models of Vizio Smart TVs.

Consider the wide range of items that today broadcast Wi-Fi or Bluetooth SSIDs and MAC addresses: cars, smart toys, tablets, mobile headsets, soda machines . . . all easily and publicly detectable. Many aggregators are also able to detect the beacons that retailers are deploying, providing detail about what stores you have been nearby, or products to which you have been in proximity.

How to Manage a Complex Consumer Privacy Landscape

Much of the current debate about the appropriate regulatory regime for ISPs has focused on whether ISPs are unique in the type or scale of data they can collect. Much of the web surfing data that ISPs can collect has been widely available in the market for more than a decade. The business trends in the data market that need to be understood are those driven by consolidation of data companies who are merging with ad tech companies or marketing platforms, the linking of devices across platforms, the additions of location and proximity data, and the uses of machine learning to enhance targeting.

How should we protect consumer privacy in this complex environment? In an ideal world, comprehensive federal privacy legislation would provide a baseline level of protection for all consumers. Given the low likelihood of this path, the FTC has a long history and deep expertise on the subject of privacy across platforms and devices. Although jurisdictional questions remain to be resolved by federal courts or by Congress, the FTC has a broad mandate to protect consumers against deceptive or unfair practices in commerce. Over the years, the agency has brought cases against ISPs, apps, major online platforms, and even most recently a Smart TV manufacturer. In 2015, the Commission created the Office of Technology Research and Investigation (OTech) to conduct technical research, investigate compliance, and provide guidance to consumers and businesses. Currently, FTC staff are examining the way unmanned aerial vehicles (UEVs) collect and handle data, and hosting an “Internet of Things Challenge” to help consumers evaluate security vulnerabilities in Smart Home devices.

Critics have pointed out that the FTC’s statutory rulemaking authority is more limited than that of other agencies. Nonetheless, the FTC has shown that it can make strong de facto “rules” by the broad manner in which it interprets its authority. In the recent Vizio case, for example, the FTC determined that sharing consumers’ TV viewing histories, linked not to names but IP addresses and device identifiers, was an unfair sharing of sensitive personal information without clear user notice and consent. This decision sets the baseline for all other Smart TV manufacturers, who now have a clearer standard for responsible data collection in the TV environment.

According to George Washington University’s Professor Daniel Solove and Samford University’s Woody Hartzog:

“The FTC privacy jurisprudence is the broadest and most influential regulating force on information privacy in United States—more so than nearly any privacy statute and any common law tort. Some assume that standards set by the FTC would be more generous to ISPs than the rules that the FCC was advancing, particularly around sensitive data. But the history of the FTC belies that argument and the agency is quite likely to use its authority to ensure ISPs set high standards for use of data about consumers. However those standards will also likely be technologically neutral, holding all the companies in the long linked data ecosystem accountable.” – “The FTC and the New Common Law of Privacy”

Connected cars, drones, wearables, smart TVs, smart homes, smart toys – all provide valuable services to consumers. But as these systems and platforms become increasingly interconnected, consumer protection requires a regulator with a broad scope and deep expertise in the advertising, data, and technology markets. The FTC has the flexibility, breadth of knowledge, and expertise to ensure that consumers are protected in this complex, data-driven world.