The Connecticut Data Privacy Act Gets an Overhaul (Again)

Co-Authored by Gia Kim, FPF U.S. Policy Intern

On June 25, Governor Ned Lamont signed SB 1295, amending the Connecticut Data Privacy Act (CTDPA). True to its namesake as the “Land of Steady Habits,” Connecticut is developing the habit of amending the CTDPA. Connecticut has long been ahead of the curve, especially when it comes to privacy. In 1788, Connecticut became the fifth state to ratify the U.S. Constitution. In 2022, it similarly became the fifth state to enact a comprehensive consumer privacy law. In 2023, it returned to that law to add heightened privacy protections for minors and for consumer health data. In 2024 and 2025, the Attorney General issued enforcement reports that included recommendations for changes to the law (some of which were ultimately included in SB 1295). Now, a mere two years since the last major amendments, Connecticut has once again passed an overhaul of the CTDPA.

This fresh bundle of amendments makes myriad changes to the law, expanding its scope, adding a new consumer right, heightening the already strong protections for minors, and more. Important changes include:

- Significantly expanded scope, through changes to applicability thresholds, narrowed exemptions, and expanded definitions;

- Changes to consumer rights, including modifying the right to access one’s personal data and a new right to contest certain profiling decisions;

- Modest changes to data minimization, purpose limitation, and consent requirements;

- New impact assessment requirements headline changes to profiling requirements; and

- Protections for minors, including a ban on targeted advertising.

These changes will be effective July 1, 2026 unless stated otherwise.

1. The Law’s Scope Is Expanded Through Changes to Applicability Thresholds, Narrowed Exemptions, and Expanded Definitions

A. Expanded Applicability

Some of the most significant changes these amendments make to the CTDPA are the adjustments to the law’s applicability thresholds, likely bringing many more businesses in scope of the law. Prior to SB 1295, controllers doing business in Connecticut were subject to the CTDPA if they controlled or processed the personal data of (1) at least 100K consumers (excluding personal data controlled or processed solely for completing a payment transaction), or (2) at least 25K consumers if they also derived more than 25% of their gross revenue from the sale of personal data. The figures in those thresholds were already common to the state comprehensive privacy laws when the CTDPA was enacted in 2022, and those same thresholds have been included in numerous additional state privacy laws enacted after the CTDPA. In recent years, however, several new privacy laws have opted for lower thresholds. SB 1295 continues that trend and goes further.

Under the revised applicability thresholds, the CTDPA will apply to entities that (1) control or process the personal data of at least 35K consumers, (2) control or process consumers’ sensitive data (excluding personal data controlled or processed solely for completing a payment transaction), or (3) offer consumers’ personal data for sale in trade or commerce. Although the lowered affected consumer threshold aligns with other states such as Delaware, New Hampshire, Maryland, and Rhode Island, the other two applicability thresholds are unique and more expansive. Given the broad definition of “sensitive data,” expanding the law’s reach to any entity that processes any sensitive data is significant as it likely implicates a vast array of businesses that were not previously in scope. Similarly, expanding the law’s reach to any entity that offers personal data for sale may implicate a wide swath of small businesses engaged in targeted advertising, given the broad definition of “sale” which includes the exchange of personal data for monetary or other valuable consideration.

In addition to the changes to the applicability thresholds, these amendments also adjust some of the law’s exemptions. Most notably, SB 1295 replaces the entity-level Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act (GLBA) exemption with a data-level exemption. This follows an emerging trend in favor of a data-level GLBA exemption, and it was one of the requested legislative changes in the Connecticut Attorney General’s 2024 and 2025 reports on CTDPA enforcement. As the GLBA entity-level exemption is removed, that change is counterbalanced by new entity-level exemptions for some other financial institutions such as insurers, banks, and certain investment agents as defined under various federal and state laws. Shifting away from the GLBA entity-level exemption is responsive to concerns that organizations like payday lenders and car dealerships were avoiding applicability under state privacy laws, which was not lawmakers’ intent.

B. New and Modified Definitions

Expanding the law’s applicability to any entity that processes sensitive data is compounded by the changes SB 1295 makes to the definition of sensitive data, which now includes mental or physical health “disability or treatment” (in addition to “condition” or “diagnosis”), status as nonbinary or transgender (like in Oregon, Delaware, New Jersey, and Maryland), information derived from genetic or biometric data, “neural data” (defined differently than in California or Colorado), financial information (focusing largely on account numbers, log-ins, card numbers, or relevant passwords or credentials giving access to a financial account), and government-issued identification numbers.

Another minor scope change in SB 1295 is the new definition of “publicly available information,” which now aligns with the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) by excluding biometric data that was collected without the consumer’s consent.

2. Changes to Consumer Rights, Including Modifying the Right to Access One’s Personal Data and a New Right to Contest Certain Profiling Decisions

A. Access

Drawing from developments in other states, SB 1295 makes several changes to the law’s consumer rights. First, SB 1295 expands the right to access one’s personal data to include (1) inferences about the consumer derived from personal data and (2) whether a consumer’s personal data is being processed for profiling to make a decision that produces any legal or similarly significant effect concerning the consumer. This is consistent with requirements under the Colorado Privacy Act regulations (Rule 4.04), which specify that compliance with an access request must include “include final [p]rofiling decisions, inferences, derivative data, marketing profiles, and other [p]ersonal [d]ata created by the [c]ontroller which is linked or reasonably linkable to an identified or identifiable individual.” The CCPA similarly specifies that personal information includes inferences derived from personal information to create a profile about a consumer, bringing such information within the scope of access requests.

Since 2023, new privacy laws in Oregon, Delaware, Maryland, and Minnesota have included a consumer right to know either the specific third parties or the categories of third parties to whom the consumer’s personal data are disclosed. Continuing that trend, SB 1295 adds a right to access a list of the third parties to whom a controller sold a consumer’s personal data, or, if that information is not available, a list of all third parties to whom a controller sold personal data. While this closely resembles the provisions in the Oregon Consumer Privacy Act and the Minnesota Consumer Data Privacy Act, SB 1295 differs from those laws in a few minute ways. First, SB 1295 concerns the third parties to whom personal data was sold, as opposed to the third parties to whom personal data was disclosed. This difference may not be consequential if the amount of third parties to whom personal data are disclosed but not “sold” (given the broad definition of “sell”) is near zero. Furthermore, unlike in Oregon’s law where the option to provide a non-personalized list of third party recipients is at the controller’s discretion, SB 1295 only allows controllers to provide the broader, non-personalized list if the controller does not maintain a list of the third parties to whom it sold the consumer’s personal data.

While the above changes expand the right to access, SB 1295 also narrows the right to access by prohibiting disclosure of certain types of personal data. Under the amendments, a controller cannot disclose the following types of data in response to a consumer access request: social security number; government-issued identification number (including driver’s license number); financial account number; health insurance or medical identification number; account password, security question or answer; and biometric data. Instead, the CTDPA now requires a controller to inform the consumer “with sufficient particularity” that the controller collected these types of personal data. Minnesota became the first state to include this requirement in its comprehensive privacy law in 2024, and Montana amended its privacy law earlier this year to include a similar requirement. This change is likely an attempt to balance a consumer’s right to access their personal data with the security risk of erroneously exposing sensitive information such as SSNs to third parties or bad actors.

B. Profiling

In addition to the changes to the access right, SB 1295 makes important amendments to profiling rights. The existing right to opt-out of profiling in furtherance of decisions that produce legal or similarly significant effects is expanded. Previously it was limited to “solely automated decisions,” whereas now the right applies to “any automated decision” that produces legal or similarly significant effects. Similarly, the reworked definition of “decision that produces any legal or similarly significant effect” now includes any decision made “on behalf of the controller,” not just decisions made by the controller. This likely expands the scope of profiling protections to intermediate and non-final decisions.

SB 1295 also adds a new right to contest profiling decisions, becoming the second state to do so after Minnesota. Under this new right, if a controller is processing personal data for profiling in furtherance of any automated decision that produced any legal or similarly significant effects concerning the consumer, and if feasible, the consumer will have the right to:

- Question the result of the profiling;

- Be informed of the reason why the profiling led to such decision;

- Review the personal data used for the profiling; and

- If the decision concerned housing, correct the inaccurate data and have the profiling decision reevaluated with corrected data.

These requirements diverge from Minnesota’s approach in a few ways. First, Connecticut’s right only applies “if feasible,” which arguably removes any implicit incentive to design automated decisions based on profiling to accommodate such rights. For example, Minnesota’s law does not have this caveat, so controllers will have to design their profiling practices to be explainable. Although this differs from Minnesota’s right, it is not wholly new language. Rather, Connecticut’s “if feasible” qualifier mirrors language in the right to appeal an adverse consequential decision under Colorado’s 2024 law regulating high-risk artificial intelligence systems (allowing for human review of adverse decisions “if technically feasible”). Second, the right to correct inaccurate personal data and have the profiling decision reevaluated is limited to decisions concerning housing. Third, SB 1295 does not include the right to be informed of actions that the consumer could have taken, and can take in the future, “to secure a different decision.”

3. Modest Changes to Controller Duties, Including Data Minimization, Purpose Limitation, and Sensitive Data Consent Requirements

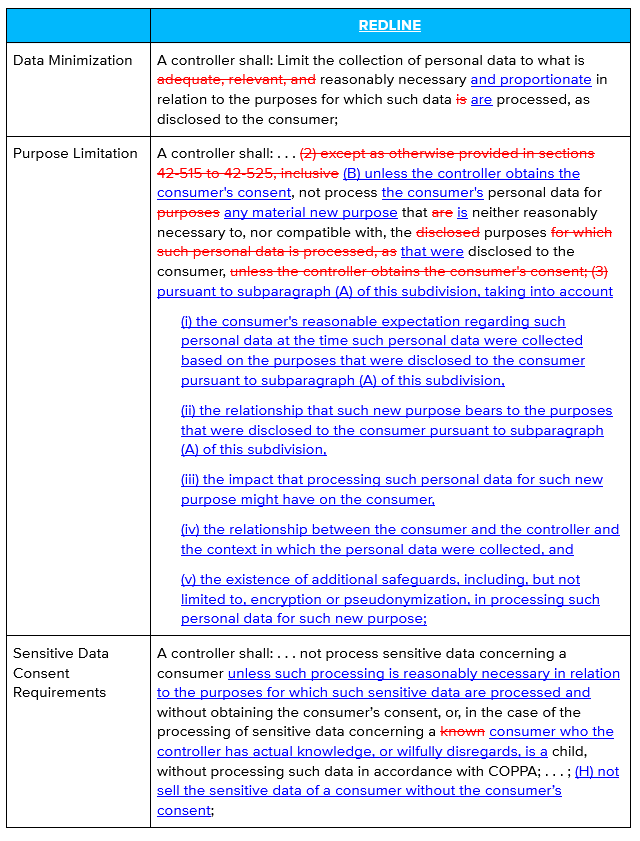

Data minimization has become a hotly contested policy issue in privacy legislation in recent years, as states explore more “substantive” requirements that tie the collection, processing, and/or sharing of personal (or sensitive) data to what is “necessary” to provide a requested product or service. At various points this year, Connecticut, Colorado, and Oregon all considered amending their existing privacy laws to include Maryland-style substantive data minimization requirements. None of these states ended up following that path, although Connecticut did rework the data minimization, purpose limitation, and consent requirements in the CTDPA.

It is not immediately clear whether these changes are more than trivial, at least with respect to data minimization and the sensitive data requirements. Changing the limit on collecting personal data from what is “adequate, relevant, and reasonably necessary” for a disclosed purpose to what is “reasonably necessary and proportionate” for a disclosed purpose may not be operationally significant. “Proportionality” is a legal term of art that is beyond the scope of this blog post. It is sufficient to say that it is doubtful that in this context “proportionate” means much more than to limit collection to what is adequate and relevant, which was the original language. Similarly, for sensitive data, controllers now have the added requirement to limit their processing to what is “reasonably necessary in relation to the purposes for which such sensitive data are processed,” in addition to getting consent for processing. This change may be trivial at best and circular at worst, depending on whether one believes that it is even possible to process data for a purpose that is not reasonably necessary to the purpose for which the data are being processed. Similarly, the law now specifies that controllers must obtain separate consent to sell sensitive data. This change is likely intended to prevent controllers from bundling requests to sell sensitive data with other consent requests for processing activities that are essential for the functionality of a product or service.

The changes are more significant with respect to purpose limitation. The core aspects of the rule remain unchanged—obtain consent for secondary uses of personal data (subject to various exceptions in the law, such as bias testing for automated decisionmaking). New in SB 1295 is (1) a new term of art (a “material new purpose”) to describe secondary uses that are not reasonably necessary to or compatible with the purposes previously disclosed to the consumer, and (2) factors to determine when a secondary use is a “material new purpose.” These factors include the consumer’s reasonable expectations at the time of collection, the link between new purpose and the original purpose, potential impacts on the consumer, the consumer-controller relationship and the context of collection, and potential safeguards. These factors are inspired by, but not identical to, those in Rule 6.08 of the Colorado Privacy Act regulations and § 7002 of the CCPA regulations, which were themselves inspired by the General Data Protection Regulation’s factors for assessing the compatibility of secondary uses in Art. 6(4).

There are other minor changes to controller duties, including a new requirement for controllers to disclose whether they collect, use, or sell personal data for the purpose of training large language models (LLMs).

4. New Impact Assessment Requirements Headline Changes to Profiling Requirements

SB 1295 expands and builds upon many of the CTDPA’s existing protections and business obligations with respect to profiling and automated decisions, affecting consumer rights, transparency obligations, exceptions to the law, and privacy by design and accountability practices. As discussed above, SB 1295—

- Expands the existing profiling opt-out right to apply to decisions other than those that are “solely automated”;

- Adds a new right to contest certain profiling decisions;

- Requires controllers disclose whether they are collecting, using, or selling personal data for the purpose of training LLMs; and

- Adds a new exception to the law, providing that nothing in the CTDPA shall restrict a controller’s ability to collect, use, or retain data for internal use to detect or correct any bias that may result from profiling, subject to certain safeguards and restrictions on reuse.

Another significant update with respect to profiling is the addition of new impact assessment requirements. Like the majority of state comprehensive privacy laws, the CTDPA already requires controllers to conduct data protection assessments for processing activities that present a heightened risk of harm, which includes profiling that presents a reasonably foreseeable risk of substantial injury (e.g., financial, physical or reputational injury). SB 1295 adds a new “impact assessment” requirement for controllers engaged in profiling for the purposes of making a decision that produces any legal or similarly significant effect concerning a consumer. An impact assessment has to include, “to the extent reasonably known by or available to the controller,” the following:

- A statement disclosing the profiling’s “purpose, intended use cases and deployment context of, and benefits afforded by,” the profiling;

- Analysis as to whether the profiling poses any “known or reasonably foreseeable heightened risk of harm to a consumer”;

- A description of the main categories of personal data processed as inputs for the profiling and the outputs the profiling produces;

- An overview of the “main categories” of personal data used to “customize” the profiling, if any;

- Any metrics used to evaluate the performance and known limitations of the profiling;

- A description of any transparency measures taken, including measures taken to disclose to the consumer that the profiling is occurring while it is occurring; and

- A description of post-deployment monitoring and user safeguards provided (e.g., oversight, use, and learning processes).

These requirements are largely consistent with similar requirements under Colorado’s 2024 law regulating high-risk artificial intelligence systems. Impact assessments will be required for processing activities created or generated on or after August 1, 2026, and they will not be retroactive.

These new provisions raise several questions. First, it is unclear whether an obligation to include information that is “reasonably known by or available to the controller” implies an affirmative duty for a controller to seek out facts and information that may not be known already but which could be identified through additional testing. Second, it is not clear when and how impact assessments should be bundled with data protection assessments, to the extent that they overlap. The law provides that a single data protection assessment or impact assessment can address a comparable set of processing operations that include similar activities. This could be read either as saying that one assessment total can cover a set of similar activities, or that one data protection assessment or impact assessment can be conducted to cover a set of similar activities but an activity (or set of activities) subject to both requirements must receive two assessments.

Impact assessments will be relevant to enforcement. Like with data protection assessments, the AG can require a controller to disclose any impact assessment relevant to an investigation. In an enforcement action concerning the law’s prohibition on processing personal data in violation of state and federal antidiscrimination laws, evidence or lack of evidence regarding a controller’s proactive bias testing or other similar proactive efforts may be relevant.

With respect to minors, there are additional steps and disclosures that must be made. If a controller conducts a data protection assessment or impact assessment and determines that there is a heightened risk of harm to minors, the controller is required to “establish and implement a plan to mitigate or eliminate such risk.” The AG can require the controller to disclose a harm mitigation or elimination plan if the plan is relevant to an investigation conducted by the AG. These “harm mitigation or elimination plans” shall be treated as confidential and exempt from FOIA disclosure in the same manner as data protection assessments and impact assessments.

5. Protections for Minors, Including a Ban on Targeted Advertising

The last major update to the CTDPA in 2023 added heightened protections for minors, including certain processing and design restrictions and a duty for controllers to use reasonable care to avoid “any heightened risk of harm to minors” caused by their service. Colorado and Montana followed Connecticut’s lead and added similar protections to their comprehensive privacy laws in recent years. SB 1295 now adjusts those protections for minors again and makes them stricter.

Under the revised provisions, a controller is entitled to a rebuttable presumption of having used reasonable care if they comply with the data protection assessment and impact assessment requirements under the law. More significant changes have been made to the processing restrictions. Previously, the law imposed several substantive restrictions (e.g., limits on targeted advertising or the sale of personal data) for minors, but allowed a controller to proceed with those activities if they obtained opt-in consent. As noted in FPF’s analysis of the 2023 CTDPA amendments, it is atypical for a privacy law to allow for consent as an alternative to certain baseline protections such as data minimization and retention limits. In narrowing the role of consent with respect to minors, SB 1295 imposes strongline baselines and privacy by design requirements with respect to children and teens:

- Processing Personal Data. Controllers cannot: (A) process minors personal data for targeted advertising or any sale of personal data; (B) process minors personal data unless the processing is reasonably necessary to provide the online service, product, or feature (“service”); (C) process minors personal data for any processing purpose other than that disclosed at the time of collection or what is reasonably necessary for and compatible with the initial purpose; or (D) process minors personal data for longer than is reasonably necessary to provide the service (with an exception for education technology).

- Collecting Precise Geolocation Data. Controllers cannot collect precise geolocation data unless (A) the data are strictly necessary for the service (if so, the collection must be limited to the time necessary to provide the service); and (B) the controller provides a signal indicating to the minor that it is collecting precise geolocation data during the collection.

The bans on targeted advertising and selling personal data of minors align with Maryland, and a recently enacted amendment to the Oregon Consumer Privacy Act banning the sale of personal data of consumers under the age of 16.

Consent is not entirely excised. The revised law still allows controllers to obtain opt-in consent to process minors’ personal data for purposes of profiling in furtherance of any automated decision made by the controller that produces legal or similarly significant effect concerning the provision or denial of certain enumerated essential goods and services (e.g., education enrollment or opportunity). Allowing minors to opt-in to such profiling may open up opportunities that would otherwise be foreclosed, especially in areas like employment, financial services, and educational enrollment which older teenagers are likely encountering for the first time as they approach adulthood. For example, some career or scholarship quizzes may rely on profiling to tailor opportunities to a teen’s interests.

* * *

Looking to get up to speed on the existing state comprehensive consumer privacy laws? Check out FPF’s 2024 report, Anatomy of State Comprehensive Privacy Law: Surveying the State Privacy Law Landscape and Recent Legislative Trends.