The State of State AI: Legislative Approaches to AI in 2025

State lawmakers accelerated their focus on AI regulation in 2025, proposing a vast array of new regulatory models. From chatbots and frontier models to healthcare, liability, and sandboxes, legislators examined nearly every aspect of AI as they sought to address its impact on their constituents.

To help stakeholders understand this rapidly evolving environment, the Future of Privacy Forum (FPF) has published The State of State AI: Legislative Approaches to AI in 2025.

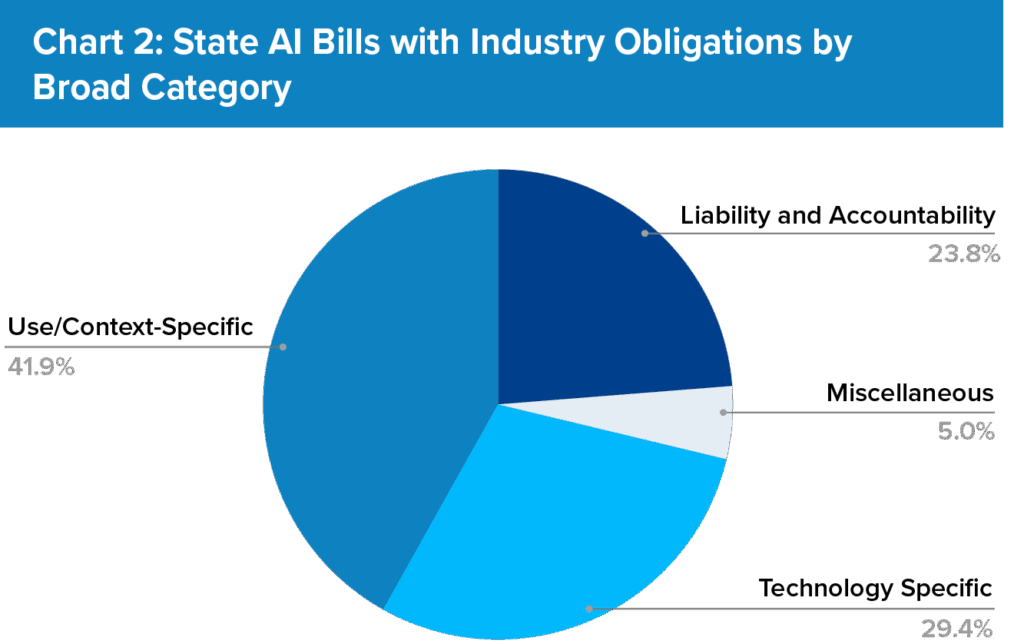

This report analyzes how states shaped AI legislation during the 2025 legislative session, spotlighting the trends and thematic approaches that steered state policymaking. By grouping legislation into three primary categories: (1) use- and context-specific measures, (2) technology-specific bills, and (3) liability and accountability frameworks, this report highlights the most important developments for industry, policymakers, and other stakeholders within AI governance.

In 2025, FPF tracked 210 bills across 42 states that could directly or indirectly affect private-sector AI development and deployment. Of those, 20 bills (around 9%) were enrolled or enacted.1 While other trackers estimated that more than 1,000 AI-related bills were introduced this year, FPF’s methodology applies a narrower lens, focusing on measures most likely to create direct compliance implications for private-sector AI developers and deployers.2

Key Takeaways

- State lawmakers moved away from sweeping frameworks regulating AI, towards narrower, transparency-driven approaches.

- Three key approaches to private sector AI regulation emerged: use and context-specific regulations targeting sensitive applications, technology-specific regulations, and a liability and accountability approach that utilizes, clarifies, or modifies existing liability regimes’ application to AI.

- The most commonly enrolled or enacted frameworks include AI’s application in healthcare, chatbots, and innovation safeguards.

- Legislatures signaled an interest in balancing consumer protection with support for AI growth, including testing novel innovation-forward mechanisms, such as sandboxes and liability defenses.

- Looking ahead to 2026, issues like definitional uncertainty remain persistent while newer trends around topics like agentic AI and algorithmic pricing are starting to emerge.

Classification of AI Legislation

To provide a framework to analyze the diverse set of bills introduced in 2025, FPF classified state legislation into four categories based on their primary focus. This classification highlights whether lawmakers concentrated on specific applications, particular technologies, liability and accountability questions, or government use and strategy. While many bills touch on multiple themes, this framework is designed to capture each bill’s primary focus and enable consistent comparisons across jurisdictions.

Table I.

| Use / Context-Specific Bills | Focuses on certain uses of AI in high-risk decisionmaking or contexts–such as healthcare, employment, and finance–as well as broader proposals that address AI systems used in a variety of consequential decisionmaking contexts. These bills typically focus on applications where AI may significantly impact individuals’ rights, access to services, or economic opportunities. Examples of enacted frameworks: Illinois HB 1806 (AI in mental health), Montana SB 212 (AI in critical infrastructure) |

| Technology-Specific Bills | Focuses on specific types of AI technologies, such as generative AI, frontier/foundation models, and chatbots. These bills often tailor requirements to the functionality, capabilities, or use patterns of each system type. Examples of enacted frameworks: New York S 6453 (frontier models), Maine LD 1727 (chatbots), Utah SB 226 (generative AI) |

| Bills Focused on Liability and Accountability | Focuses on defining, clarifying, or qualifying legal responsibility for use and development of AI systems utilizing existing legal tools, such as clarifying liability standards, creating affirmative defenses, or authorizing regulatory sandboxes. These aim to support accountability, responsible innovation, and greater legal clarity. Examples of enacted frameworks: Texas HB 149 (regulatory sandbox), Arkansas HB 1876 (copyright ownership of synthetic content) |

| Government Use and Strategy Bills | Focuses on requirements for government agencies’ use of AI that have downstream or indirect effects on the private sector, such as creating standards and requirements for agencies procuring AI systems from private sector vendors. Examples of enacted frameworks: Kentucky SB 4 (high-risk AI in government), New York A 433 (automated employment decision making in government) |

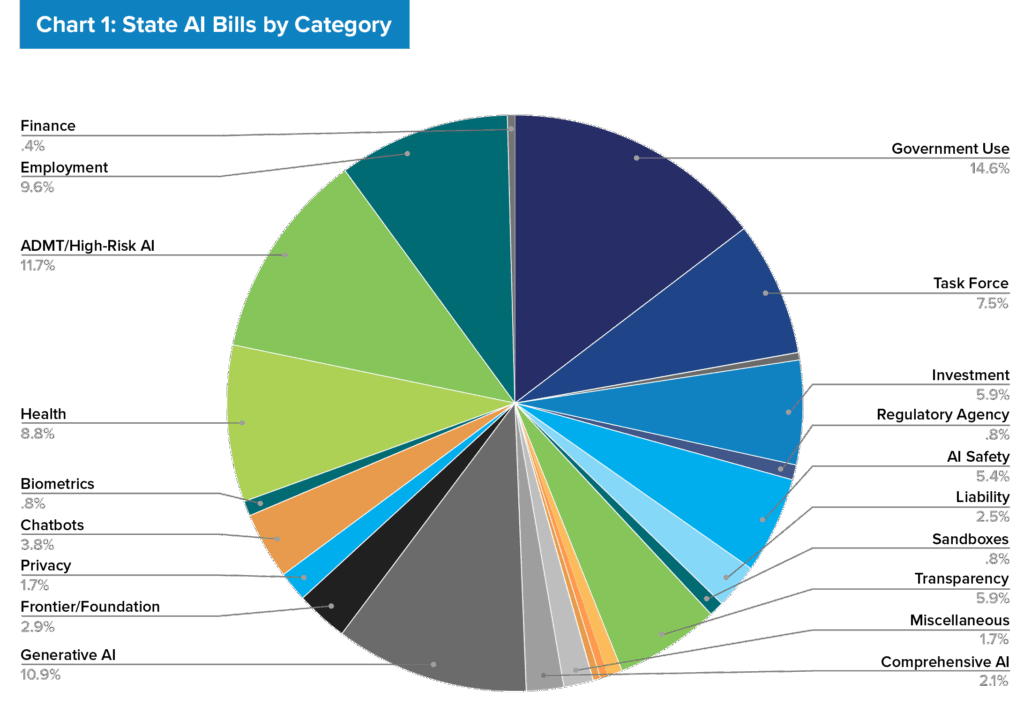

Table II. Organizes the 210 bills tracked by FPF’s U.S. Legislation Team in 2025 across 18 subcategories.

Table III. Organizes the 210 bills tracked by FPF’s U.S. Legislation Team in 2025 into overarching themes, excluding bills focused on government use and strategy that do not set direct industry obligations. Bills in the “miscellaneous” category primarily reflect comprehensive AI legislation.

Use or Context-Specific Approaches to AI Regulation

In 2025, nine laws were enrolled or enacted and six additional bills passed at least one chamber that sought to regulate AI based on its use or context.

- Focus on health-related AI applications: Legislatures concentrated on AI in sensitive health contexts, especially mental health and companion chatbots, often setting disclosure obligations. These health-specific laws primarily focus on limiting or guiding AI use by licensed professionals, particularly in mental health contexts. Looking beyond enrolled or enacted measures, nearly 9% of all introduced AI-related bills tracked by FPF in 2025 focused specifically on healthcare. From a compliance perspective, most prohibit AI from independently diagnosing patients, making treatment decisions, or replacing human providers, and many impose disclosure obligations when AI is used in patient communications.

- High-risk frameworks arose only through amendments to existing law: In contrast to 2024, when Colorado enacted the Colorado Artificial Intelligence Act (CAIA), an AI law regulating different forms of “high-risk” systems used in consequential decision making, no similarly broad legislation was passed in 2025. Several jurisdictions advanced “high risk” approaches through amendments to existing laws or rulemaking efforts–many of which predate Colorado’s AI law but reflect a similar focus on automated decision-making systems across consequential decisionmaking contexts. These include amendments to existing data privacy laws’ provisions on automated decision making under the California Privacy Protection Agency’s (CPPA) regulations, Connecticut’s SB 1295 (enacted), and New Jersey’s ongoing rulemaking.

- Growing emphasis on disclosures: User-facing disclosures became the most common safeguard, with eight of the enrolled or enacted laws and regulations requiring that individuals be informed when they are interacting with, or subject to, decisions made by an AI system.

- Shift toward fewer governance requirements: Compared to 2024 proposals, 2025 legislation shifted away from compliance mandates, like impact assessments, in favor of transparency measures. For the few laws that did include governance-related processes, the obligations were generally “softer,” such as being tied to an affirmative defense (e.g. Utah’s HB 452, enacted) or satisfied through adherence to federal requirements (e.g. Montana’s SB 212, enacted).

Technology-Specific Approaches to AI Regulation

In 2025, ten laws were enrolled or enacted and five additional bills passed at least one chamber that targeted specific types of AI technologies, rather than just their use contexts.

- Chatbots as a key legislative focus: Several new laws focused on chatbots—particularly “companion” and mental health chatbots—introducing compliance requirements for user disclosure, safety protocols to address risks like suicide and self-harm, and restrictions on data use and advertising. Chatbots drew heightened legislative attention following recent court cases and high-profile incidents involving chatbot that allegedly promoted suicidal ideation to youth. As a result, several of these bills, like New York’s S-3008C (enacted), introduce safety-focused provisions, including directing users to crisis resources. Additionally, six of the seven key chatbot bills include a requirement for chatbot operators to notify users that the chatbot is not human, in efforts to promote user awareness.

- Frontier/foundation models regulation reintroduced: California and New York revived frontier model legislation (SB 53 and the RAISE Act, enrolled), building on 2024’s California’s SB 1047 (vetoed) but with narrower scope and streamlined requirements for written safety protocols. Similar bills were introduced in Rhode Island, Michigan, and Illinois, centered on preventing “catastrophic risks” from the most powerful AI systems, like large-scale security failures that could lead to human injury or harms to critical infrastructure.

- Generative AI proposals centered on labeling: A majority of generative AI bills in 2025 focused on content labeling—either required disclosures visible to users at the time of interaction, or a more technical effort of tagging of provenance or training data to enhance content traceability—to address risks of deception and misinformation. Bills include: California’s AB 853 (enrolled), New York’s S 6954 (proposed), California’s SB 11 (enrolled), and New York’s S 934 (proposed).

Liability and Accountability Approaches to AI Regulation

This past year, eight laws were enrolled or enacted and nine notable bills passed at least one chamber that focused on defining, clarifying, or qualifying legal responsibility for use and deployment of AI systems. State legislatures tested different ways to balance liability, safety, and innovation.

- Clarifying liability regimes for accountability: Across numerous states, lawmakers looked to affirmative defenses, or legal claims that allow defendants to dismiss lawsuits based on certain grounds, as a solution for incentivizing responsible AI practices while maintaining flexibility and reducing legal risks for businesses. Examples include: Utah’s HB 452 (enacted) allowing an affirmative defense if a provider maintained certain AI governance measures and California’s SB 813 (proposed) allowing AI developers to use certified third-party audits as an affirmative defense in civil lawsuits. Legislators also sought to update privacy and tort statutes to address AI-specific risks, such as Texas’ TRAIGA amendment (enacted) of the Texas biometric privacy law to account for AI training.

- Prioritization of innovation-focused measures: States experimented with regulatory sandboxes that allow controlled AI development, with the enactment of new regulatory sandboxes in Texas and Delaware, along with the first official sandbox agreement under Utah’s 2024 AI Policy Act (SB 149). Other legislation, such as Montana’s SB 212 (enacted), introduced “right to compute” provisions to protect AI development and deployment.

- Enforcement tools and defense strategies: Legislatures expanded Attorney General investigative powers (such as civil investigative demands) in bills including Texas’ TRAIGA (enacted) and Virginia HB 2094 (vetoed). A variety of other defense mechanisms were introduced, including specific protections for whistleblowers, as represented in California’s SB 53 (enrolled).

Looking Ahead to 2026

As the 2026 legislative cycle begins, states are expected to revisit unfinished debates from 2025 while turning to new and fast-evolving issues. Frontier/foundation models, chatbots, and health-related AI will remain central topics, while definitional uncertainty, agentic AI, and algorithmic pricing signal the next wave of policy debates.

- Definitional Uncertainty: States continue to diverge in how they define artificial intelligence itself, as well as categories like frontier models, generative AI, and chatbots. Definitional variations, such as compute thresholds for “frontier” systems or qualifiers in generative AI definitions, are shaping which technologies fall under regulatory scope. These differences will become more consequential as more bills are enrolled, expanding the compliance landscape.

- Agentic AI: Legislators are beginning to explore “AI agents” capable of autonomous planning and action, systems that move beyond generative AI’s content creation and towards more complex functions. Early governance experiments include Virginia’s “regulatory reduction pilot” and Delaware’s agentic AI sandbox, but few bills directly address these agents. Existing risk frameworks may prove ill-suited for agentic AI, as harms are harder to trace across agents’ multiple decision nodes, suggesting that governance approaches may need to adapt in 2026.

- Algorithmic pricing: States are testing ways to regulate AI-driven pricing tools, with bills targeting discrimination, transparency, and competition. New York enacted disclosure requirements for “personalized algorithmic pricing” (S 3008, enacted), while California (AB 446 and SB 384, proposed), Colorado, and Minnesota floated their own frameworks. In 2026, lawmakers may focus on more precise definitions or stronger disclosure or prohibition measures amid growing legislative activity on algorithmic pricing.

Conclusion

In 2025, state legislatures sought to demonstrate that they could be laboratories of democracy for AI governance: testing disclosure rules, liability frameworks, and technology-specific measures. With definitional questions still unsettled and new issues like agentic AI and algorithmic pricing on the horizon, state legislatures are poised to remain active in 2026. These developments illustrate both the opportunities and challenges of state-driven approaches, underscoring the value of comparative analysis as policymakers and stakeholders weigh whether, and in what form, federal standards may emerge. At the same time, signals from federal debates, increased industry advocacy, and international developments are beginning to shape state efforts, pointing to ongoing interplay between state experimentation and broader policy currents.

- Upon publication of this report, bills in California and New York are still awaiting gubernatorial action. This total is limited to bills with direct implications for industry and excludes measures focused solely on government use of AI or those that only extend the effective date of prior legislation. ↩︎

- This report excludes: bills and resolutions that merely reference AI in passing; updates to criminal statutes; and legislation focused on areas like elections, housing, agriculture, state investments in workforce development, and public education, which are less likely to involve direct obligations for companies developing or deploying AI technologies. ↩︎