It’s Raining Privacy Bills: An Overview of the Washington State Privacy Act and other Introduced Bills

By Pollyanna Sanderson (Policy Counsel), Katelyn Ringrose (Christopher Wolf Diversity Law Fellow) & Stacey Gray (Senior Policy Counsel)

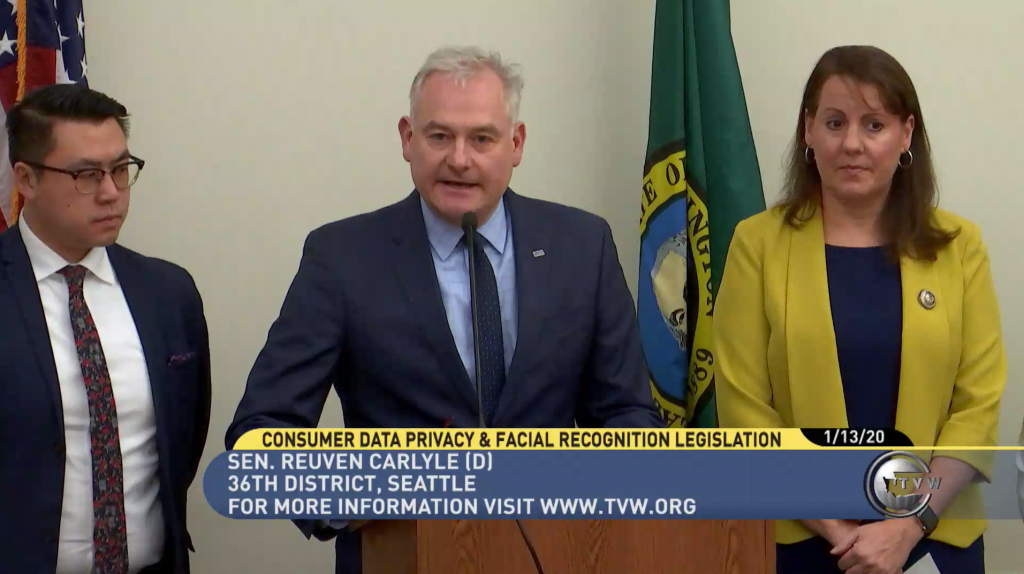

Today, on the first day of a rapid-fire 2020 legislative session in the state of Washington, State Senator Carlyle has introduced a new version of the Washington Privacy Act (WPA). Legislators revealed the Act during a live press conference on January 13, 2020 at 2:00pm PST. Meanwhile, nine other privacy-related bills were introduced into the House today by Representative Hudgins and Representative Smith.

If passed, the Washington Privacy Act would enact a comprehensive data protection framework for Washington residents that includes individual rights that mirror and go beyond the rights in the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA), as well as a range of other obligations on businesses that do not yet exist in any U.S. privacy law.

“The Washington Privacy Act is the most comprehensive state privacy legislation proposed to date,” said Jules Polonetsky, CEO of the Future of Privacy Forum. “The bill addresses concerns raised last year and proposes strong consumer protections that go beyond the California Consumer Privacy Act. It includes provisions on data minimization, purpose limitations, privacy risk assessments, anti-discrimination requirements, and limits on automated profiling that other state laws do not.”

Earlier Senate and House versions of the Washington Privacy Act narrowly failed to pass last year in the 2019 legislative session. Read FPF’s comments on last year’s proposal. The version introduced today contains strong provisions that largely align with the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), and commercial facial recognition provisions that start with a legal default of affirmative consent. Nonetheless, legislators must work within a remarkably short time-frame to pass a law that can be embraced by both House and Senate within the next six weeks of Washington’s legislative session.

Below, FPF summarizes the core provisions of the bill, which if passed would go into effect on July 31, 2021. The Act would be a holistic, GDPR-like comprehensive law that: (1) provides protections for residents of Washington State; (2) grants individuals core rights to access, correct, delete, and port data; (3) creates rights to opt out of sale, profiling, and targeted advertising; (4) creates a nuanced approach to pseudonymised data; (5) imposes obligations on processors and controllers to perform risk assessments; (6) creates collection, processing, and use obligations; and (7) requires opt-in consent for the processing of sensitive data. In addition, the Act contains provisions for controllers and processors utilizing facial recognition services.

Read the Bill Text HERE. Read the 9 other bills introduced today at the end of this blog post (Below).

Update (1/21/20): A substitute bill was released on January 20 by Senator Carlyle and cosponsors (see PSSB 6281). At 10:00am on January 23, the Senate committee on Environment, Energy & Technology will hold a hearing on this and other bills.

1. Jurisdictional and Material Scope

The Act would provide comprehensive data protections to Washington State residents, and would apply to entities that 1) conduct business in Washington or 2) produce products or services targeted to Washington residents. Such entities must control or process data of at least 100,000 consumers; or derive 50% of gross revenue from the sale of personal data and process or control personal data of at least 25,000 consumers (with “consumers” defined as natural persons who are Washington residents, acting in an individual or household context). The Act would not apply to state and local governments or municipal corporations.

The Act would regulate companies that process “personal data,” defined broadly as “any information that is linked or reasonably linkable to an identified or identifiable natural person” (not including de-identified data or publicly available information “information that is lawfully made available from federal, state, or local government records”), with specific provisions for pseudonymous data (see below, Core consumer rights).

2. Individual Rights to Access, Correct, Delete, Port, and Opt-Out of Data Processing

The Act would require companies to comply with basic individual rights to request access to their data, correct or amend that data, delete their data, and access it in portable format (“portable and, to the extent technically feasible, readily usable format that allows the consumer to transmit the data… without hindrance, where the processing is carried out by automated means”). These rights would not be permitted to be waived in contracts or terms of service, and would be subject to certain limitations (for example, retaining data for anti-fraud or security purposes).

Along with these core rights, the Act would also grant consumers the right to explicitly opt out of the processing of their personal data for the purposes of targeted advertising, the sale of personal data, or profiling in furtherance of decisions that produce legal, or similarly significant, effects. Such effects include the denial of financial and lending services, housing, insurance, education enrollment, employment opportunities, health care services, and more. Unlike the CCPA, the Act would not prescribe specific opt out methods (like a “Do Not Sell My Information” button on websites), but instead require that opt-out methods be “clear and conspicuous.” It would also commission a government study on the development of technology, such as a browser setting, browser extension, or global device setting, for consumers to express their intent to opt out.

For all of these individual rights, companies are required to take action free of charge, up to twice per year, within 45-90 days (except in cases where requests cannot be authenticated or are “manifestly unfounded or excessive”). Importantly, the law would also require that companies establish a “conspicuously available” and “easy to use” internal appeals process for refusals to take action. With the consumer’s consent, the company must submit the appeal and an explanation of the outcome to the Washington Attorney General, whether any action has been taken, and a written explanation. The Attorney General must make such information publicly available on its website. When consumers make correction, deletion, or opt out requests, the Act would oblige controllers to take “reasonable steps” to notify third parties to whom they have disclosed the personal data within the preceding year.

Finally, the Act would prohibit companies from discriminating against consumers for exercising these individual rights. Such discrimination could include the denial of goods or services, charging different prices or rates for goods or services, or providing a different level of quality of goods and services.

3. Obligations for De-identified and Pseudonymous Data

Under the Act, companies processing “pseudonymous data” would not be required to comply with the bulk of the core individual rights (access, correction, deletion, and portability) when they are “not in a position” to identify the consumer, subject to reasonable oversight. Notably, the Act defines pseudonymous data consistently with the GDPR’s definition of pseudonymization, as “personal data that cannot be attributed to a specific natural person without the use of additional information, provided that such additional information is kept separately and is subject to appropriate technical and organizational measures to [protect against identification].” This is also consistent with the Future of Privacy Forum’s Guide to Practical Data De-Identification. Pseudonymous data is often harder to authenticate or link to individuals, and can carry lessened privacy risks. For example, unique pseudonyms are frequently used in scientific research (e.g., in a HIPAA Limited Dataset, John Doe = 5L7T LX619Z).

In addition, companies may refuse to comply with requests to access, correct, delete, or port data if the company: (A) is not reasonably capable of associating the request with the personal data, or it would be unreasonably burdensome to associate the request with the personal data; (B) does not use the personal data to recognize or respond to the data subject, or associate the personal data with other data about the same specific consumer; and (C) does not sell personal data to any third party or otherwise voluntarily disclose the personal data to any third party other than a processor (service provider).

Importantly, other requirements of the overall bill, including Data Protection Assessments (below), and the right to Opt Out of data processing for targeted advertising, sale, and profiling (above) would still be operational for pseudonymous data.

Finally, the Act would not apply to de-identified data, defined as “data that cannot reasonably be used to infer information about, or otherwise be linked to, an identified or identifiable natural person, or a device linked to such person,” subject to taking reasonable measures to protect against re-identification, including contractual and public commitments. This definition aligns with the FTC’s longstanding approach to de-identification.

4. Obligations of Processors (Service Providers)

In a structure that parallels the GDPR, the Act distinguishes between data “controllers” and data “processors,” establishing different obligations for each. Almost all of the provisions of the Act involve obligations that adhere to a controller, defined as “natural or legal person which, alone or jointly with others, determines the purposes and means of the processing of personal data.”

Data processors, on the other hand, “natural or legal person who processes personal data on behalf of a controller,” must adhere (as service providers) to controllers’ instructions and help them meet their obligations. Notwithstanding controller instructions, processors must maintain security procedures that take into account the context in which personal data is processed; ensure that individual processors understand their duty of confidentiality, and may only engage a subcontractor once the controller has had the chance to object. At the request of the controller, processors must delete or return personal data. Processors must also aid in the creation of data protection assessments.

5. Transparency (Privacy Policies)

The Act would require companies to provide a Privacy Policy to consumers that is “reasonably accessible, clear, and meaningful,” including making the following disclosures:

- (i) the categories of personal data processed by the controller;

- (ii) the purposes for which the categories of personal data are processed;

- (iii) how and where consumers may exercise their rights;

- (iv) the categories of personal data that the controller shares with third parties; and

- (v) the categories of third parties with whom the controller shares personal data.

Additionally, if a controller sells personal data to third parties or processes data for certain purposes (i.e. targeted advertising), they would be required to clearly and conspicuously disclose such processing, as well as how consumers may exercise their right to opt out of such processing.

6. Data Protection Assessments

Companies would be required under the Act to conduct confidential Data Protection Assessments for all processing activities involving personal data, and again any time there are processing changes that materially increase risks to consumers. In contrast, the GDPR requires Data Protection Impact Assessments only when profiling leads to automated decision-making having a legal or significant effect upon an individual (such as credit approval), when profiling is used for evaluation or scoring based on aspects concerning an individual’s economic situation, health, personal preferences or interests, reliability or behavior, location or movements, or when it is conducted at large-scale on datasets containing sensitive personal data.

Under the WPA, in weighing benefits against the risks, controllers must take into account factors such as reasonable consumer expectations, whether data is deidentified, the context of the processing, and the relationship between the controller and the consumer. If the potential risks of privacy harm to consumers are substantial and outweigh other interests, then the controller would only be able to engage in processing with the affirmative consent of the consumer (unless another exemption applies, such as anti-fraud measures and research).

7. Sensitive Data

Companies must obtain affirmative, opt-in consent to process any “sensitive” personal data, defined as personal data revealing:

- racial or ethnic origin, religious beliefs, mental or physical health condition or diagnosis, sexual orientation, or citizenship or immigration status;

- genetic or biometric data for the purpose of uniquely identifying a natural person;

- personal data from a known child; or

- specific geolocation data (defined as “information that directly identifies the specific location of a natural person with the precision and accuracy below 1750 ft.”)

Although the Act requires consent to process data from a “known child,” an undefined term, it notably also exempts data covered by the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA) and entities that are compliant with the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA). The Act defines a child as a natural person under age thirteen, meaning it does not follow the approach of CCPA and other bills around the country that extend child privacy protections to teenagers.

8. Collection, Processing, and Use Limitations

In addition to consumer controls and individual rights, the Act would create additional obligations on companies that align with the GDPR:

- Data Minimization & Purpose Specification – Controller’s collection of personal data must be “adequate, relevant, and limited” to what is necessary in relation to the specified and express purposes for which they are processed.

- Reasonable Security – Appropriate to the volume and nature of the personal data at issue, controllers must establish, implement, and maintain reasonable administrative, technical, and physical data security practices to protect the confidentiality, integrity, and accessibility of personal data.

- Use Limitations – The Act would also create a duty to avoid secondary uses of data, absent consent, unless that processing is necessary or compatible with the specified or express purposes for which the data was initially gathered.

The obligations imposed by the Act would not restrict processing personal data for a number of specified purposes. Those exemptions include cooperating with law enforcement agencies, performing contracts, providing requested products or services to consumers, processing personal data for research, consumer protection purposes, and more. If processing falls within an enumerated exception, that processing must be “necessary, reasonable, and proportionate” in relation to a specified purpose. Controllers and processors are also not restricted from collecting, using, or retaining data for specific purposes such as conducting internal product research, improving product and service functionality, or performing internal operations reasonably aligned with consumer expectations.

9. Enforcement

The Act would not grant consumers a private right of action. Instead, it would give the Attorney General exclusive authority to enforce the Act. The Act would cap civil penalties for controllers and processors in violation of the Act at $7,500 per violation. A “Consumer Privacy Account,” in the state treasury, would contain funds received from the imposition of civil penalties. Those funds would be used for the sole purpose of the office of privacy and data protection. The Attorney General would also be tasked with compiling a report evaluating the effectiveness of enforcement actions, and any recommendations for changes.

10. Commercial Facial Recognition

In addition to its baseline requirements, the Act contains provisions specifically regulating commercial uses of facial recognition. The Act would require affirmative, opt in consent as a default requirement, and place heightened obligations on both controllers and processors of commercial facial recognition services, particularly with respect to accuracy and auditing, with a focus on preventing unfair performance impacts. A limited exception is provided for using this technology for uses such as to track the unique number of users in a space, when data is not maintained for more than 48 hours and users are not explicitly identified.

Definitions

The Act provides a number of core definitions that are relevant only to the facial recognition provisions (Section 18, the final section of the bill). Given the standalone nature of this section of the overall bill, the definitions can be very impactful. The term “facial recognition service” is defined as technology that analyzes facial features and is used for identification, verification, or persistent tracking of consumers in still or video images.

Additional definitions are as follows:

- “Facial template” is the machine-extracted image from such a service.

- “Facial recognition” encompasses both verification and identification.

- “Verification” is matching a specific consumer previously enrolled (also known as one-to-one matching), and

- “Identification” is seeking to identify an unknown consumer based on searching for a match in a gallery of enrolled images (also known as one-to-many matching).

- “Enrollment” is the process of creating a facial template (or taking an existing one) and adding it into a gallery.

- “Persistent tracking” is the use of a facial recognition service to track consumer movements without recognizing that consumer. Such tracking becomes “persistent” as soon as either: the facial template is subject to a facial recognition service for more than forty-eight hours; or the data created by the facial recognition service is linked to any other data making the consumer identified or identifiable.

Additional Duties on “Processors” and “Controllers” of Facial Recognition Services

The Act would place affirmative duties on processors, or service providers (see above for definitions of controller and processor under the Act), when they provide facial recognition services. Those duties include enforcing current provisions against illegal discrimination, as well as providing an API or other means for controllers and third parties to conduct fairness and accuracy tests. If such tests reveal unfair performance differences (e.g. bias based on a protected characteristic), the processor must develop and implement a plan to address those differences.

Controllers must also take affirmative steps to post notice in public spaces where facial recognition services are deployed; obtain consent from consumers prior to enrollment in a service operating in physical premises open to the public; ensure meaningful review for potentially harmful uses of the service; test the service and take reasonable steps to ensure quality standards; and engage in staff training. Conspicuous public notice includes, at a minimum, the purpose for which the technology is deployed and information about where consumers can obtain additional information (e.g. a link for consumers to exercise their rights).

Consent would not be required for enrolling images for security or safety purposes, but the consumer must have engaged in or be suspected of engaging in criminal activity (e.g. shoplifting); the controller must review the safety/security database no less than biannually and remove templates from individuals no longer under suspicion or who have been in the database for more than three years; and, finally, the controller must have an internal process whereby a consumer may correct or challenge enrollment. Furthermore, controllers must ensure that decisions which could pose legal or significant harms (e.g. the loss of employment opportunities, housing, etc.) are subject to meaningful human review.

Finally, the Act would prohibit controllers from disclosing personal data obtained from a facial recognition service to law enforcement, unless: required by law in response to a warrant, subpoena or legal order; when necessary to prevent or respond to an emergency involving danger of death or serious physical injury to any person, upon a good faith belief by the controller; or to send information to the national center for missing and exploited children. In addition to these duties, controllers must also comply with consumer requests outlined elsewhere in the Act.

Insight: Senator Nguyen (jointly with Senator Carlyle and others) have introduced a separate bill regulating state and local government agency uses of facial recognition technologies. In a recent news article, he stated that he did so in order to avoid getting “caught up in any potential political fight.”

OTHER WASHINGTON STATE HOUSE BILLS INTRODUCED TODAY

Washington legislators have been busy drafting a number of other consumer privacy bills. The following nine House Bills, filed by Representatives Smith (D) and Hudgins (D) were also introduced on January 13, 2020 and are intended to accompany the WPA. These bills would:

- grant individuals exclusive property rights in their own biometric identifiers (including any biological, physiological, or behavioral traits that are uniquely attributable to a single individual). (House Bill 2363)

- expand consumer rights and corporate responsibilities, in the name of “consumer empowerment,” and would enforce penalties of up to $10,000 (plus attorney’s fees) for civil violations. (House Bill 2364)

- require all connected devices to have a consumer friendly sticker informing consumers (including children) of the device’s ability to transmit user’s data to the device manufacturer or any separate business entity. (House Bill 2365)

- make the Washington State chief privacy officer an elected position, and task the CPO with educating consumers, researching best practices, providing privacy training for state agencies, and consulting with stakeholders. (House Bill 2366)

- prohibit the use of deceptive bots for commercial purposes, making the use of such bots a per se violation of the Washington Privacy Act. (House Bill 2396) (Rep. Hudgins only)

- prohibit posting statements online of financial affairs filed by a professional staff member of the legislature. (House Bill 2398)

- require controllers to achieve written consent from consumers prior to retaining voice information, and require all voice recognition feature manufacturers to prominently inform users that their devices may process or collect personal data. (House Bill 2399)

- require the office of privacy and data protection to conduct annual privacy reviews of state agencies. (House Bill 2400)

- require employers that utilize AI in hiring decisions to inform potential applicants of those technologies and obtain consent. (House Bill 2401)

Did we miss anything? Let us know at [email protected] as we continue tracking developments in Washington State.