Event Recap: Dublin Privacy Symposium 2021, Designing for Trust: Enhancing Transparency & Preventing User Manipulation

Key Takeaways

- The biggest challenge to increase UX transparency may be encouraging people to make deliberate decisions from a UX design perspective.

- Even designers’ color and shape choices in UI can be subtle ‘dark patterns’ that might even prevent, e.g., color-blind users from understanding the options at hand.

- Organizations should ask themselves whether they should be collecting certain data in the first place, in line with the minimization principle.

- Organizations need to take steps to prevent user manipulation, both by UX/UI (e.g., cookie banners) and by algorithms.

On June 23, 2021, The Future of Privacy Forum (FPF) hosted the first edition of its annual Dublin Privacy Virtual Symposium: Designing for Trust: Enhancing Transparency & Preventing User Manipulation. FPF organized the event in cooperation with the Dublin Chapter of Women in eDiscovery. Participants zoomed in on the question: What elements and design principles generally make user interfaces clear and transparent? Experts also discussed web design examples regarding user information and control, including what scholars increasingly refer to as ‘manipulative design’ or ‘dark patterns.’

The symposium included two keynote speakers and a panel discussion. Graham Carroll, Head of Strategy at The Friday Agency addressed the first keynote, followed by a keynote by Dr. Lorrie Cranor (researcher at Carnegie Mellon University’s Cylab). The keynote speakers joined the panel discussion with six other panelists: Diarmaid Mac Aonghusa (Founder and Managing Director at Fusio.net), Dylan Corcoran (Assistant Commissioner at the Irish Data Protection Commission, or ‘DPC’), Stacey Gray (Senior Counsel at FPF), Dr. Denis Kelleher (Head of Privacy EMEA at LinkedIn), Daragh O Brien (Founder and Managing Director at Castlebridge), and Dr. Hanna Schraffenberger (researcher at Radboud University’s iHub). Dr. Rob van Eijk (FPF’s Managing Director for Europe) moderated the symposium.

Below we provide a summary of (1) the first keynote on dark patterns, (2) the second keynote on how (not) to convey privacy choices with icons and links, and (3) the panel discussion.

You can view the recording of the event here.

Keynote 1: ‘Dark patterns’: from mere annoyance to deceitfulness

Graham Carroll explained that his work involved assisting Friday’s corporate clients in understanding and implementing best practices around improving user experience (UX) design for consent and transparency. He underlined that being transparent about privacy and data processing is crucial for user trust. Furthermore, he stressed the importance of understanding the motivations in online interactions, e.g., publishers, advertisers, and users.

Carroll defined ‘dark patterns’ as deceptive UX or user interface (UI) interactions designed to mislead users when making online choices—for example, leading users to consent for ancillary personal data processing when subscribing to a newsletter.

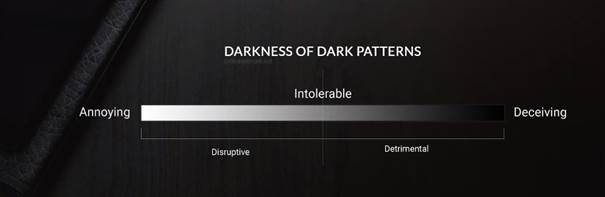

While companies wish to increase revenue while remaining compliant, their users want to complete their goals and feel secure while doing it quickly. Carroll’s research shows that users tend to take a path of least resistance when they are asked to make a choice online. A key element of Carroll’s presentation was a scale by Nagda, Y. (2020) depicting consequences for users, i.e., going from annoying to deceiving (Figure 1). Carroll argued that forcing users to close a pop-up upon entering a website may be considered less disruptive than a more complicated account cancelation process.

Therefore, Carroll stated that some manipulative designs would be more deserving of a legal ban than others, which would make it easier for regulators to enforce and for companies to comply with the law. He also mentioned an online resource listing and advancing a definition of different types of ‘dark patterns.’

Carroll then devoted a particular focus to the online advertising sector, stating that the latter was prolific in creating ‘dark patterns’ in cookie consent banners. In that context, he offered several examples, such as banners without a ‘reject’ option and others where the ‘manage cookies’ or ‘more options’ button was smaller or used a less prominent color than the ‘accept’ or ‘agree’ button.

Carroll conducted some user testing to understand users’ behaviors around cookie consent and ultimately improved their banners’ design and UX. The results showed that were only presented with ‘accept’ and ‘manage cookies’ options, 92% of users accepted. Even when offered a ‘reject’ button, 85% did so. When the cookie banner was made unobtrusive during the website browsing, many users (36%) ignored it. Remarkably, in a separate qualitative test, the results shown by Carroll were quite different. When users were asked what they would do if they were offered a cookie banner, a significant number stated that they always rejected non-essential cookies. This demonstrates that, verbally, people were more willing to err on the side of privacy caution, which was not aligned with the study’s quantitative results.

In Carroll’s view, such results show that users tend to take the ‘path of least resistance’ when browsing. Therefore, design practices involve offering clear and transparent notices that give users real options. We also learned that the needs of the visually impaired should be taken into account, e.g., using contrast.

In closing, Carroll briefly touched upon transparency and consent designs in IoT devices, e.g., smart TVs and virtual voice assistants.

Keynote 2: Toggles, $ Signs, and Triangles: How (not) to Convey Privacy Choices with Icons and Links

Dr. Cranor, presented the results of her research group’s work on privacy icons under the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA). The research showed that icons are not often great at clarity, language, and cultural independence. Furthermore, icons have shown not to be intuitive, especially when describing abstract concepts such as privacy. They may, then, require a short explanation to accompany them .

The group’s research stemmed from Chapter 20 of the initial California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) proposal. Section 999.315 on opt-out requests from personal information sales mentions an optional button, allowing users to exercise such rights. Therefore, Cylab decided to send the California Attorney General (AG) some design proposals for the button. The project started with the icon ideation phase, including testing different word combinations next to the icons. Three concepts for icon design were tested: choice/consent (checkmarks/checkboxes), opting-out (usually involving arrows, movement, etc.), and do-not-sell (with money symbology). In this exercise, the group sought to avoid overlap with the Digital Advertising Alliance’s (DAA) privacy rights icons.

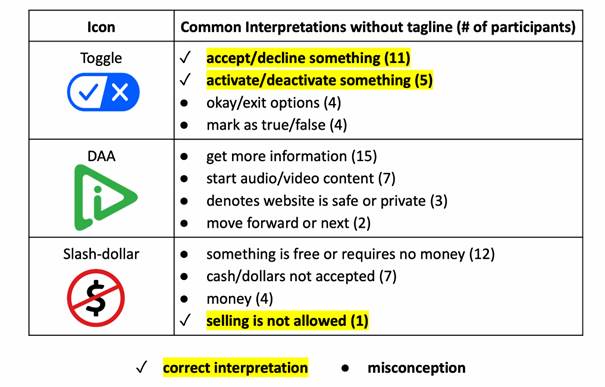

Initially, the first icons were tested with 240 MTurks. The first half was shown icons with accompanying words, while the other half was presented only with icons. When asked what they thought would happen if they clicked each button, the second half showed difficulty interpreting several icons in the absence of words. In this respect, opt-out signs were generally confusing, while only a few consent and do-not-sell icons were intelligible for some participants.

After refining the initial icons, notably by adding color (e.g, red opt-out icons, blue consent toggle), the team conducted a second test. This time the blue toggle was the top performer (Figure 2).

Then, the group conducted another study, testing 540 MTurk participants’ comprehension of taglines (words). In that context, participants showed more understanding of more extended taglines, like ‘Do Not Sell My Info Choices’, than shorter ones, like ‘Do Not Sell’. Afterward, the team performed some even more extensive user testing of icon and tagline combinations. The tests revealed some user misconceptions, like users assuming that the ‘Personal Info Choices’ would allow them to choose their preferred payment method in an online store.

In the end, the researchers concluded that none of the icons were very good at conveying the intended layered privacy messages. However, they found that icons increased the likelihood that users noticed the link/text next to them. They recommended the California AG to adopt the same blue toggle for both ‘Privacy Options’ and ‘Do Not Sell my Personal Info.’ After the California legislature included a different toggle in the draft CCPA, the team conducted a new study demonstrating that the latest toggle was not as clear to users as the one proposed by Cylab. Eventually, the initial blue toggle suggestion was included in the final text of the CCPA, even if it remains optional and generally not adopted by websites developed in California.

Finally, Dr. Cranor made some closing remarks and outlined the research’s key takeaways. The team concluded that privacy icons should be accompanied by text to increase their effectiveness. It also recommended incorporating user testing, for which Cylab is currently developing guidelines, into the policy-making process. Dr. Cranoralso expressed a desire to achieve globally recognizable privacy icons, albeit it looks like a complex endeavor. Outside of the policy-making sphere, she identified three priorities for increasing user transparency: (i) creating a habit of evaluating the effectiveness of transparency mechanisms before roll-out; (ii) defining standards and best practices around tested mechanisms, putting aside the need for each website to decide by itself; and (iii) incorporating automation, to reduce the users’ burden and choice fatigue (e.g., centralizing choices in the browser or device settings).

Panel discussion: Analyzing trends to increase UX transparency

Dr. Hanna Schraffenberger started by saying that the biggest challenge is encouraging people to make deliberate decisions from a UX design perspective. According to the researcher, users should not be forced to stop and think about each step they take online, especially given that they invariably take the same options (e.g., accepting or rejecting cookies). To make her point, Dr. Schraffenberger shared that her team invited research participants to a test in which they would be given no good reason to click ‘agree’, but still did. To the team’s surprise, this happened even when the ‘reject’ was made the most prominent option. According to the panelist, this shows that users are overwhelmingly prone to agree without questioning their options. Dr. Schraffenberger’s team’s goal is to make users slow down before proceeding with their browsing in a given website, notably by introducing design friction. An example of such friction would be forcing users to drag an icon to their preferred option on the screen. However, the speaker revealed challenges in measuring the user deliberation process in this context.

Daragh O Brien suggested that designers’ color and shape choices in UI can be subtle ‘dark patterns.’ He added that such choices might even prevent, e.g., color-blind users from understanding the options at hand. O Brien offered the European Data Protection Supervisor’s website as a bad example in that regard, given that all buttons were displayed in the same blue color. Therefore, the panelist called upon designers to question their user perception assumptions before implementing UI. O Brien also pointed to text-to-speech capabilities and succinct and straightforward explanations of the purpose of the processing as tools to account for the needs of all users. In reply to the speaker’s observations, both Dr. Cranor and Carroll stepped in. The former acknowledged research does not always consider user accessibility needs. The latter admitted that such requirements are challenging for UX designers and companies due to their cost implications. O Brien mentioned that organizations need to understand that not considering vulnerable audiences’ needs is a deliberate choice that can have consequences. He reminded the audience that intelligibility is a legal requirement that stems from data protection law.

Diarmaid Mac Aonghusa started off by stating that most cookie management solutions providers should redesign their products from scratch. On that note, the panelist argued that users should not be pushed to make online decisions out of frustration or consent fatigue by being constantly asked whether they accept being tracked all over the web. By asking the audience to imagine how the same experience would feel every time they changed TV channels, Mac Aonghusa argued that current privacy regulations are well-intentioned but not fit for the digital sphere. The speaker suggested reaching a consensus around a globally applicable setting for all websites at the browser level. This should aim to respect users’ choices, even if that could disappoint individual website providers.

Dylan Corcoran focused on data processing transparency towards users of IoT devices. In that respect, Corcoran mentioned that it is the controllers’ responsibility to determine the best practical way to inform their customers, considering user psychology in reaction to UX design. According to the panelist, articles 12 to 14 General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) should not be taken as a checklist, as controllers should also account for the target audience’s cognition and understanding. That ultimately allows the former to determine whether the information passed on to data subjects is presented in a clear, concise, and understandable manner. Providers should also ensure users understand non-primary data processing purposes (e.g., integrations with third-party services, analytics, Software Development Kits used by developers, etc.). Data Privacy Officers and compliance teams are expected to engage with their appointers’ designers and programmers to embed transparency into their products and services.

Dr. Denis Kelleher started by aligning with Carroll’s earlier remarks, stating that transparency is key to obtaining and retaining customer trust. This is particularly true on what concerns data handling practices. With the maturing of the data protection field, companies are being pushed to increase their levels of transparency. According to Dr. Kelleher, this is corroborated by European Union (EU) Data Protection Authority’s (DPAs) decisions during the first three years of application of the GDPR and by disclosure requirements in the European Commission’s Artificial Intelligence Act proposal. He mentioned the EDPS’ and the European Data Protection Board’s (EDPB) recent comments to such a proposal. The speaker also talked about the industry’s eagerness to see what the final text of the ePrivacy Regulation will end up mandating on transparency. Dr. Kelleher said organizations need to understand better what level of detail users want in clear and concise privacy notices. The panelist also stressed that the industry is expecting to see EDPB guidance on transparency. The Board’s 2021-2022 Work Programme lists Guidelines and practical recommendations on data protection in social media platform interfaces as upcoming work.

Stacey Gray remarked whether and to what extent US consumer protection laws provide legal boundaries and transparency standards for potentially manipulative UX design practices. She stressed that the US had an opportunity going forward to learn from the EU’s successes and failures in this sphere. She also observed that legal obligations on interface design might not prevent users from making irrational decisions. There are some consumer protections under US law against ‘dark patterns,’ as remedies against deception, coercion, and manipulation are provided by federal and state laws. Gray also stated that the relevant literature seems to agree that users are given a choice to decline. However, it may be burdensome, and users are nudged to accept that online players’ practices would not be forbidden. Levels of tolerance for nudging in the law tend to depend on different factors, including: (i) users’ awareness of the choices they can make; (ii) users’ ability to avoid making a choice entirely; (iii) the content of the actual choice. Currently, two US states have passed omnibus privacy laws banning dark patterns: the California Privacy Rights Act and Colorado Privacy Act (which will come into effect in 2025) if signed by the Governor. Lastly, Gray pointed to the CCPA’s requirement that companies do not engage in ‘dark patterns’ to disincentivize people from exercising their opt-out right.

During a final round of interventions, all speakers were given a chance to react to each others’ remarks and to reply to the audience’s questions. Dr. Cranor highlighted that research on nudging had shown a fine line between legitimate persuasion and pressure/bullying in the online world. Nonetheless, she admitted that the persuasion’s end goal (e.g., pushing people to get vaccinated v. to accept tracking) is not neutral.

On a different note, but agreeing with the points made by Dr. Cranor during her earlier presentation, Corcoran took the view that organizations should test the effectiveness of their transparency measures before implementing them. This should also allow them to comply with the GDPR’s accountability principle. For that purpose, Corcoran mentioned MTurks and A/B testing as valuable tools.

Dr. Schraffenberger reinforced her earlier position, stressing that designers should develop interfaces that help users make good choices online. This, according to the panelists, may involve engaging with experts from other domains, such as psychology and ethics.

Both Dr. Kelleher and Mac Aonghusa agreed that organizations need to take steps to prevent user manipulation, both by UX/UI (e.g., cookie banners) and by algorithms. For users, what companies seek their consent for and what happens to their data after collection should be more precise, albeit there are limitations regarding the amount of information that can be delivered on a screen. Dr. Kelleher also mentioned that a change in the data protection paradigm, shifting from strict transparency to controller accountability and responsible data use, may be in order.

To wrap up, O Brien called for considering data subjects’ concerns and expectations regarding the processing of their personal data when building UI. According to the panelist, organizations should first ask themselves whether they should be collecting certain data in the first place, in line with the minimization principle. On a bright note, O Brien stressed that, sometimes, less is more, especially when it comes to more fine-grained datasets. In the speaker’s view, it should be the privacy community’s duty to convey such a message to their boards and clients.

To learn more, watch the recording of the event.

Other resources:

Highlights of FPF’s March 2021 event Manipulative UX Design and the Role of Regulation.

One of the 2020 FPF Privacy Papers for Policymakers Award winners: Dark Patterns at Scale: Findings from a Crawl of 11K Shopping Websites, by Arnuesh Mathur, Gunes Acar, Michael Friedman, Elena Lucherini, Jonathan Mayer, Marshini Chetty, and Arvind Narayanan.