Introduction to the Conformity Assessment under the draft EU AI Act, and how it compares to DPIAs

The proposed Regulation on Artificial Intelligence (‘proposed AIA’ or ‘the Proposal’) put forward by the European Commission is the first initiative towards a comprehensive legal framework on AI in the world. It aims to set rules on specific AI applications in certain contexts and does not intend to regulate AI technology in general. The proposed AIA includes specific provisions applicable to AI systems depending on the level of risk to the health, safety, and fundamental rights of individuals that they pose. These scalable rules vary from banning certain AI applications to providing heightened obligations related to high-risk AI systems – such as strict quality rules for training, validation, and testing datasets, to setting in place transparency rules for certain AI systems.

A key obligation imposed on high-risk AI systems are Conformity Assessments (CA), which providers of such systems must perform before they are placed on the market. But what are Conformity Assessments? What do they review and how do they compare to Data Protection Impact Assessments (DPIAs)? In this blogpost, and after a short contextual introduction (1), we break down the CA legal obligation into its critical characteristics (2), aiming to understand: when is a CA required, who is responsible for performing a CA, in what way should the CA be performed, and whether there are other actors involved in the process. We then explain the way that the CA relates to the General Data Protection Regulation’s (GDPR) DPIA obligation (3) and we conclude with 4 key takeaways on the AIA’s CA (4).

1. Context: The EU AI Act and the universe of existing EU law it has to integrate with

The proposed AIA, according to its Preamble, is a legal instrument primarily targeted at ensuring a well functioning internal market in the EU that respects and upholds fundamental rights. 1 Being a core part of the EU Digital Single Market Strategy, the drafters of the AIA explain in a Memorandum accompanying it that the Act aims to avoid fragmentation of the internal market by setting harmonised rules on the development and placing on the market of ‘lawful, safe and trustworthy AI systems’. One of the announced underlying purposes of the initiative is to ensure legal certainty for all actors in the AI supply chain.

The proposed AIA is built on a risk-based approach. The legal obligations of responsible actors depend on the classification of AI systems based on the risks they present to health, safety, and fundamental rights. Risks vary from ‘unacceptable risks’ (that lead to prohibited practices), ‘high risks’ (which trigger a set of stringent obligations, including conducting a CA), ‘limited risks’ (with associated transparency obligations), to ‘minimal risks’ (where stakeholders are encouraged to build codes of conduct).

The draft AIA is being introduced in an already existing system of laws that regulate products and services intended to be placed on the European market, as well as laws that concern the processing of personal data, the confidentiality of electronic communications or intermediary liability legal regimes.

For instance, the proposed AIA and its obligations aim to align with the processes and requirements of laws that fall under the New Legislative Framework (NLF) in order to ‘minimize the burden on operators and avoid any possible duplication’ (Recital 63). The application of the AIA is intended to be without prejudice to other laws and its drafters state in the Preamble that it is laid down consistently with the Regulations that are explicitly mentioned.

In the EU context, the CA obligation is not new. CAs are also part of several EU laws on product safety. For example, in cases where the AI system is a safety component of a product which falls under the scope of NLF laws, a different CA may have already taken place.

1.1 The definition of an AI system

The proposed AIA defines an AI system as ‘software that is developed with one or more of the techniques and approaches listed in its Annex I and can, for a given set of human-defined objectives, generate outputs such as content, predictions, recommendations, or decisions influencing the environments they interact with’ (Article 3(1)).

- Whether a software qualifies as an AI system under the Proposal depends on if it falls under Annex I of the draft Regulation, which includes a finite list of software such as machine learning approaches, logic- and knowledge-based approaches, and statistical approaches. According to Article 4 AIA, this Annex can be amended by the European Commission following the adoption of delegated acts in light of market and technological developments.

- An AI system can be designed to operate with varying levels of autonomy and be used on a stand-alone basis or as a component of a product, irrespective of whether the system is physically integrated into the product (embedded) or serves the functionality of the product without being integrated therein (non-embedded).

1.2 High-risk AI systems

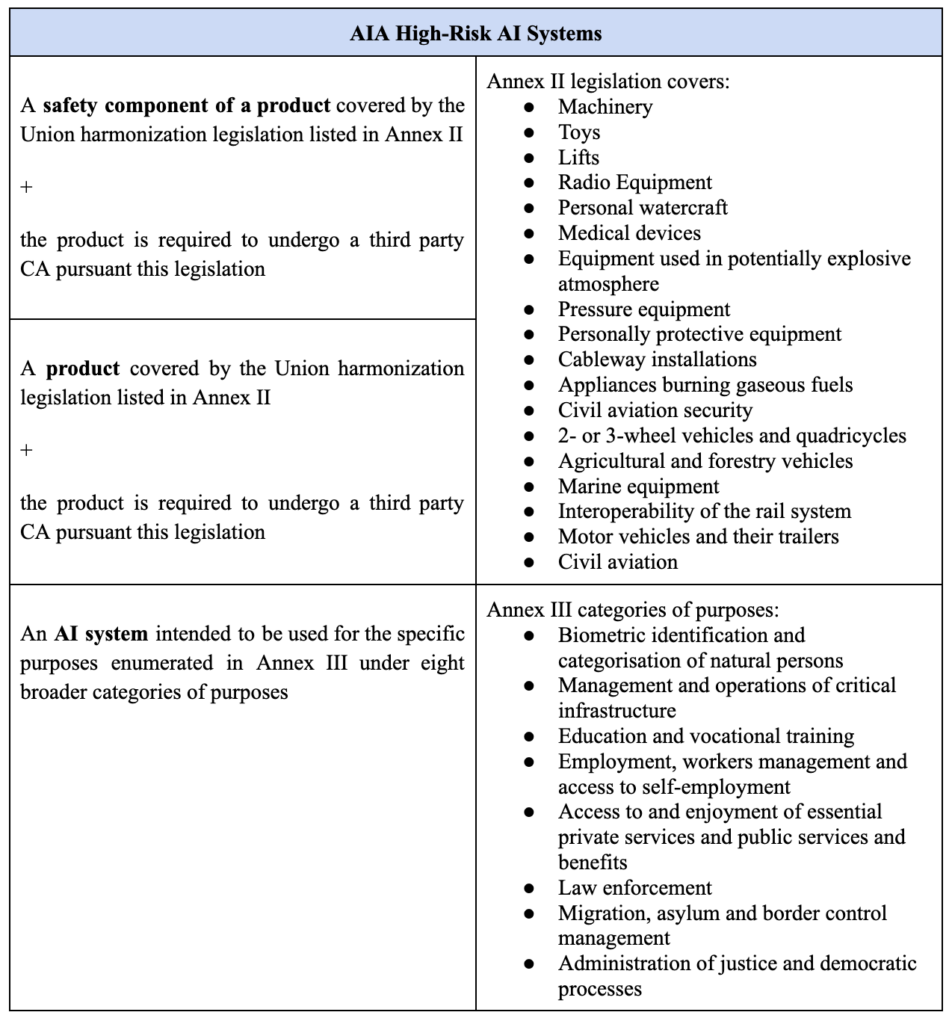

The AIA offers no definition of a ‘high-risk AI system’, but it classifies specific AI uses as high-risk and enumerates them in relation to Annexes II and III of the Proposal (see Table 1 below).

Annex III to the AIA, which details high-risk AI systems, can be amended by the European Commission following the conditions set by Article 7. For example, where an AI system poses a risk of harm to health and safety, or a risk of adverse impact on fundamental rights, the Annex could be amended.

The current Presidency of the Council, held by the Czech Republic, has proposed to narrow down the list of high-risk AI systems as part of the current legislative negotiations on the text of the AIA.

2. The Conformity Assessment obligation, explained

The Conformity Assessment (CA) is a legal obligation designed to foster accountability under the proposed AIA that only applies to AI systems classified as ‘high-risk’. According to its AIA definition, CA is the ‘process of verifying whether the requirements set out in Title III, Chapter 2 of this Regulation relating to an AI system have been fulfilled’, with Title III containing provisions that only apply to high-risk AI systems.

2.1 Requirements for High-risk AI systems that also form the object of the CA

The requirements the AIA provides for high-risk AI systems are ‘necessary to effectively mitigate the risks for health, safety and fundamental rights, as applicable in the light of the intended purpose of the system’ (Recital 43). They relate to:

a) The quality of data sets used to train, validate and test the AI systems; the data sets have to be ‘relevant, representative, free of errors and complete’, as well as having ‘the appropriate statistical properties (…) as regards the persons or groups of persons on which the high-risk AI systems is intended to be used’ (Recitals 44 and 45, and Article 10),

b) Technical documentation (Recital 46, Article 11, and Annex IV),

c) Record-keeping in the form of automatic recording of events (Article 12),

d) Transparency and the provision of information to users (Recital 47 and Article 13),

e) Human oversight (Recital 48 and Article 14), and

f) Robustness, accuracy and cybersecurity (Recitals 49 to 51, and Article 15).

Importantly, most of these requirements must be embedded in the design of the high-risk AI system. Except for the technical documentation that should be drawn up by the provider, the other requirements need to be taken into consideration from the earliest stages of designing and developing the AI system. Even if the provider is not the designer/developer of the system, they still need to make sure that requirements under that Chapter are embedded in the system to achieve conformity status.

The AIA also establishes a presumption of compliance with the requirements for high-risk AI systems, where a high-risk AI system is in conformity with relevant harmonised standards. In case harmonised standards do not exist or are insufficient, the European Commission may adopt common specifications, conformity with which also leads to such a presumption of compliance. In cases where a high-risk AI system has been certified or for which a statement of conformity has been issued under a cybersecurity scheme pursuant to the Cybersecurity Act, there is a presumption of conformity with the AIA’s cybersecurity requirements, as long as the certificate or statement covers them.

2.2 When should the CA be performed?

A CA has to be performed prior to placing an AI system on the EU market, which means prior to making it available (i.e., supplying for distribution or use), or prior to putting an AI system into service, which means prior to its first use in the EU market, either by the system’s user or for [the provider’s] own use.

Additionally, a new CA has to be performed when a high-risk AI system is substantially modified, which is when a change affects a system’s compliance with the requirements for high-risk AI systems or results in a modification to the AI system’s intended purpose. However, there is no need for a new CA when a high-risk AI system continues to learn after being placed on the market or put into service as long as these changes are pre-determined at the moment of the initial CA and are described in the initial technical documentation.

The proposed AIA introduces the possibility of derogating from the obligation to perform a CA ‘for exceptional reasons of public security or the protection of life and health of persons, environmental protection and the protection of key industrial and infrastructural assets’, under strict conditions (see Article 47).

2.3 Who should perform the CA?

The CA is primarily performed by the ‘provider’ of a high-risk AI system, but it can also be performed in specific situations by the product manufacturer, the distributor, or the importer of a high-risk AI system, as well as by a third party.

The ‘provider’ is ‘a natural or legal person, public authority, agency, or other body that develops an AI system or that has an AI system developed with a view to placing it on the market or putting it into service under its own name or trademark, whether for payment or free of charge’ (Article 3(2)). The provider can be, but does not have to be the person who designed or developed the system.

There are two cases where the provider is not the actor responsible for performing a CA, where instead it is the duty of:

a) the Product Manufacturer, if, cumulatively:

- the high-risk AI system relates to products for which the laws in Annex II section A apply,

- the system is placed on the market or put into service together with the product, AND

- under the name of the product manufacturer (Article 24, and Recital 55).

b) The ‘Distributor’, ‘Importer’ or ‘any other third-party’, if:

- they place on the market or put into service a high-risk AI system under their name or trademark,

- they modify the intended purpose (as determined by the provider) of a high-risk AI system already placed on the market or put into service, in case of which the initial provider is no longer considered the provider for the purposes of the AIA, OR if

- they make a substantial modification to the high-risk AI system. In this case, the initial provider is also no longer considered the provider (Article 28).

2.4 The CA can be conducted internally or by a third party

There are two ways in which a CA can be conducted – either internally, or by a third party.

In the internal CA process, it is the provider (or the distributor/importer/other third-party) who performs the CA. The third-party CA is performed by an external ‘notified body’. These ‘notified bodies’ are conformity assessment bodies that satisfy specific requirements provided by AIA in Article 33 and have been designated by the national notifying authorities.

Typically, the rule is to have an internal CA, with the drafters of the AIA arguing that providers are better equipped and have the necessary expertise to assess AI systems’ compliance. (Recital 64). A third party CA is required only for AI systems intended to be used for the real-time and post remote biometric identification of people that are not applying harmonized standards or the common specifications of Article 41. Additionally, if the high risk AI system is the safety component of a product and specific laws enumerated in Annex II, Section A apply to it, the provider must follow the type of CA process stipulated in the relevant legal act.

FPF Training: The EU’s Proposed AI Act

The EU’s Artificial Intelligence (AI) Act is in the final stages of adoption in Brussels, and will be the first piece of legislation worldwide regulating AI. Join us for an FPF Training virtual session to learn about the act’s extraterritorial reach, the legal implications for providers and deployers of AI, and more.

2.5 How is the CA performed?

In the case of the internal CA process, the provider/distributor/importer/other third-party has to:

- verify that the established quality management system is in compliance with the requirements depicted in Article 17 (entitled ‘Quality Management System’),

- examine the information in the technical documentation to assess whether the requirements for high risk AI systems are met, and

- verify that the design and development process of the AI system and its post-market monitoring (Article 61) is consistent with the technical documentation.

After the responsible entity performs an internal CA, it draws up a written EU declaration of conformity for each AI system (Article 19(1)). Annex V of the AIA enumerates the information to be included in the EU declaration of conformity. This declaration should be kept up-to-date for 10 years after the system has been placed on the market or put into service and a copy of it should be provided to the national authorities upon request.

The provider or other responsible entity also has to affix a visible, legible, and indelible CE marking of conformity according to the conditions set in Article 49. This process must also abide by the conditions set out in Article 30 of Regulation (EC) No 765/2008, notably that the CE marking shall be affixed only by the provider/other entity responsible for the conformity of the system. To conclude the process, the provider has to draw up an EU declaration form – containing, inter alia, a description of the conformity assessment procedure performed (Article 19(1)).

In the case of a third-party CA, the notified body assesses the quality management system and the technical documentation, according to the process explained in Annex VII. The third-party CA process is activated after the responsible entity applies to the notified body of their choice (Article 43(1)). Annex VII enumerates the information that should be included in the application to the notified body. Both the quality management system and the technical documentation must be in the provider’s application.

- If the notified body finds the high-risk AI system to be in conformity with the requirements, it will issue an EU technical documentation assessment certificate (Article 44), which has limited time validity and can be suspended or withdrawn by the notified body. Similarly to the internal CA, under the third-party CA process, the provider then has to draw up the EU declaration of conformity and affix the CE marking of conformity. To conclude the process, the provider has to draw up an EU declaration form – containing, inter alia, a description of the conformity assessment procedure performed (Article 19(1)).

- In case the notified body assesses that the high-risk AI system is not in conformity with the requirements for high-risk AI systems, this has to be communicated and explained in detail to the provider or other responsible entity. Article 45 grants the provider (or any actor with a legitimate interest) the right to appeal against the decision of the notified body. In this case, the responsible actor must take the necessary corrective actions. These actions may vary from bringing the system back to conformity with the requirements, to withdrawing or recalling the system from the market (Article 61).

2.6 The CA is not a one-off exercise

Providers must establish and document a post-market monitoring system, which aims to evaluate the continuous compliance of AI systems with the AIA requirements for high-risk AI systems. The post-market monitoring plan can be part of the technical documentation or the product’s plan. Additionally, in the case of a third-party CA, the notified body must carry out periodic audits to make sure that the provider maintains and applies the quality management system.

3. Conformity Assessment & Data Protection Impact Assessment (DPIA)

This section analyzes comparatively the proposed AIA’s CA and the DPIA as introduced in the GDPR. Although both obligations require an assessment to be performed on high risk processing operations (in the case of a DPIA) and AI systems (in the case of the CA), there are both differences and commonalities to be highlighted.

The DPIA is a legal obligation under the GDPR which requires that the entity responsible for a personal data processing operation (the ‘controller’) carry out an assessment of the impact of the envisaged processing on the protection of personal data, particularly where the processing in question is likely to result in a high risk to the rights and freedoms of individuals, prior to the processing taking place (Article 35 GDPR).

Under the GDPR, the data controller is the actor that determines the purposes and the means of the data processing operation. The data controller is responsible for compliance with the law, for assessing whether a DPIA shall be performed, and for performing any DPIA it determines is necessary. Under the AIA, and as explained in Section 2.3, the CA is primarily conducted by the ‘provider’ of a high-risk AI system (or by the product manufacturer, the distributor or the importer, or a third party, when specific conditions are met).

Notably, in the context of AI systems, it will likely often be the case that the AIA’s ‘user’ will qualify as a ‘data controller’ under the GDPR, and when this is the case the ‘user’ will be responsible for any required DPIA, including those on the qualifying processing operations underpinning an AI system, even if a different entity is the ‘provider’ responsible for the CA required by the AIA. In these situations, it may be the case that the relevant parts of the CA conducted by the provider of the AI system (such as those related to the compliance with the data quality and cybersecurity requirements) may inform the DPIA the user has to conduct detailing the risks posed by the processing activity and the measures taken to address those risks.

In their Joint Opinion on the AIA, the European Data Protection Supervisor (EDPS) and the European Data Protection Board (EDPB) recommend that the ‘provider’ should perform an initial risk assessment on an AI system paying due regard to the technical characteristics of the system – so ‘providers’ do retain some responsibility even if they are not a given system’s GDPR ‘data controller’. If an actor is both the AIA ‘provider’ and the GDPR ‘data controller’ with regard to an AI system that will process personal data, then that actor will perform both the CA and the DPIA.

3.1 Conditions that trigger the CA and DPIA legal obligations

The DPIA is triggered in cases where an activity qualifies as ‘processing of personal data’ and is ‘likely to result in a high risk to the rights and freedoms of natural persons’. Whether processing is likely to result in a high risk or not, a preliminary assessment (otherwise called ‘screening test’) needs to be made by the data controller. The law itself, as well as the European Data Protection Board, have provided guidance as to the types of processing that require a DPIA under the GDPR, but they are not overly prescriptive. Additionally, national supervisory authorities have published lists (so called ‘blacklists’) of processing operations that always require a DPIA to be conducted (see, for example, the lists of the Polish and Spanish DPAs). These lists often include processing operations which can be associated with an AI system as defined under the proposed AIA, such as ‘evaluation or assessment, including profiling and behavioral analysis’, or ‘processing that involves automated decision-making or that makes a significant contribution to such decision-making’.

In return, the proposed AIA specifies which AI systems qualify as ‘high-risk’ and therefore require a CA under the AIA. It does not leave it to the discretion of the responsible entity to assess whether a CA is required. Importantly, for a CA to be triggered it does not matter whether personal data is processed, even though it might be processed as part of the training and use of the AI system; it suffices that an AI system falls under the scope of AIA and qualifies as ‘high-risk’.

In situations where a high-risk AI system involves processing personal data, it likely requires a DPIA as well as a CA. In these situations, depending on whether the responsible entity to conduct a CA is also a controller under the GDPR, then both a DPIA and a CA will be conducted by the same entity, and the question of whether there is any overlap between the two assessments arises. Both processes are risk-based assessments of particular systems with separately enumerated requirements; in order to avoid unnecessary duplication of work or contradictory findings, it is likely that one can feed into the other.

3.2 Scope of the assessments

Each assessment has a different scope. For a DPIA, the data controller must assess the ‘processing operation’ in relation to the risks it poses to the rights and freedoms of natural persons. More specifically, the data controller must look into the nature, scope, context, and purposes of the processing, and its necessity and proportionality to its stated aim.

For the CA, the provider must assess whether a system or product has been designed and developed according to the specific AIA requirements imposed on high-risk AI systems. Some of these requirements have data protection implications, particularly those related to the quality of the data sets when the data used for training, validation and testing are personal data. Among other obligations, for all high-risk AI systems such data must be examined in view of possible biases, must be subjected to a prior assessment of ‘availability, quantity, and suitability’, and must also be ‘relevant, representative, free of errors, and complete’.

These bias analysis requirements also implicate the GDPR, which specifically imposes additional restrictions on the processing of special category data (for example, data related to religious beliefs, racial or ethnic origin, health, sexual orientation) via Article 9. Processing special category data is generally prohibited by the GDPR unless the processing meets one of a closed list of exemptions; the AIA’s requirement to examine training, validation, and testing data for biases brings instances where processing to detect bias requires the use of such data within the GDPR exemption authorizing “processing … necessary for reasons of substantial public interest, on the basis of Union or Member State law” so long as that the AIA’s requirements that it include ‘state-of-the-art security and privacy-preserving measures such as pseudonymisation, or encryption where anonymisation may significantly affect the purpose’ are also followed. The AIA further requires that high risk training, validation, and testing data include, to the extent required by the intended purpose, ‘the characteristics or elements that are particular to the specific geographical, behavioral or functional setting within which the high-risk AI system is intended to be used’.

These requirements are intertwined with the lawfulness, fairness, purpose limitation, and accuracy principles of the GDPR. Additionally, requirements for high-risk AI systems broadly intended to impose ‘appropriate data governance and management practices’ on such systems such as those related to transparency and to human oversight may draw parallels with some of the requirements imposed by the GDPR on solely automated decision-making requiring the provision of information about the logic involved therein, and the right to human intervention.

These requirements for high-risk AI systems are part of the scope of a CA. They are demonstrably intertwined with GDPR provisions insofar the training, validation, and testing data are personal data. As a result, there will likely be instances where a CA and a DPIA are relevant for each other – and where both are required, both must be conducted affirmatively (either prior to the processing activity or prior to the placement of a high-risk AI system on the market).

3.3 Content of the assessment

When conducting a DPIA, the data controller has to identify risks to rights and freedoms, assess the risks in terms of their severity and the likelihood of them being materialized, and to finally decide on the appropriate measures that will mitigate the high risks. In contrast, a CA requires examining whether an AI system meets specific requirements set by the law: (1) whether the training, validation, and testing of data sets meet the quality criteria referred to in Article 10 AIA, (2) whether the required technical documentation is in place, (3) whether the automatic recording of events (‘logs’) while the high-risk AI systems is operating is enabled, (4) whether transparency of the system’s operation is ensured and enables users to interpret the system’s output and use it appropriately, (5) whether human oversight is possible, and (6) whether accuracy, robustness and cybersecurity are guaranteed.

3.4 Aim of the legal obligations

The DPIA is a major tool for accountability that forces data controllers to make decisions on the basis of risks. It also forces them to report on the decision-making process. The ultimate goal of the DPIA is to hold data controllers accountable for their actions and to guarantee a more effective protection of individuals’ rights. The CA, on the other hand, is of a somewhat different nature. The CA aims to guarantee compliance with certain requirements which, according to Recitals 42 and 43, constitute mitigation measures for systems that introduce high risks. The CA aims to guarantee that the mitigation measures (so the requirements) set by the law are complied with.

Key Takeaways

The proposed AIA is currently being reviewed separately by the EU co-legislators – the European Parliament and the Council of the EU – as part of the legislative process. In that context, the CA process as proposed by the Commission may suffer changes. For instance, Brando Benifei, the Act’s co-rapporteur in the European Parliament, has revealed a preference for enlarging the cases where a third-party CA would be required. Nonetheless, we note that the CA is a well-established process with a long history in the EU, and an important EU internal market practice, which may prevent misalignment with other EU legal instruments where CA are mandatory. Having this background in mind, here are our key takeaways:

- The AIA aims to uphold legal certainty and avoid fragmentation and confusion for actors involved in the AI supply chain. This becomes clear when looking at how the proposed AIA: (a) builds on existing laws (e.g., by requiring CE marking and referring to legal acts under the NLF); and (b) aligns most of its definitions with other relevant legal acts (e.g., ‘conformity assessment’, ‘provider’, and ‘placing on the market’). The structure and the content of the proposed AIA reminds us that it is part of a system of laws that regulate products and services placed on the EU market.

- While the DPIA and the CA obligations are different in scope, content, and aims, there are also some areas in which they are connected and might even overlap, whenever high-risk AI systems involve processing of personal data. One of the essential questions is who is the entity responsible for conducting each of them. The ‘provider’ is usually the entity responsible for conducting CAs, and providers of high-risk AI systems that process personal data are more likely to have the role of ‘processors’ under the GDPR in relation to the ‘user’ of an AI system, as indicated by the EDPS and EDPB in their Joint Opinion. Only GDPR controllers have the obligation to conduct DPIAs. Controllers are more likely to be ‘users’ of high-risk AI systems under the AIA. Processors would thus have to assess their datasets against bias, for accuracy, and against whether they account for relevant characteristics for a specific geographical, behavioral, and functional context as part of the CA process, which goes beyond the obligations that they have under the GDPR in relation to the same personal data. CAs of high-risk AI systems involving processing of personal data can complement or be relied on by controllers conducting DPIAs. The AIA and its CA obligation might thus fill in a gap with regard to the responsibilities of providers of systems and data controllers who use these systems to process personal data. However, as we showed in Section 3 above, if an actor is both the AIA ‘provider’ and the GDPR ‘data controller’ with regard to an AI system that will process personal data, then that actor will perform both the CA and the DPIA.

- Although the CA process may not change, some other elements of the AIA are highly contentious. The definition of what an AI system is and the final classification of AI systems as ‘high-risk’ are at the heart of the current debates around the proposed AIA. In addition, there have been calls for clarifying the role of each actor under the AIA, with some stakeholders calling for increased obligations of AI systems’ users. Due to the complexity of the AI supply chains, it is crucial to identify the actors and their relevant responsibilities.

- Making good use of the existing resources in order to avoid duplication of processes and efforts is among the AIA’s aims. Except for the requirement to align the CA processes applicable to safety components of a product and to the product itself, the proposed AIA encourages internal CA more than third-party CA, due to the arguably stronger expertise of AI systems’ providers. It also encourages the adoption of standards or common technical specifications that could lead to presumption of compliance of high-risk AI systems with mandatory requirements.

Editors and Contributors: Lee Matheson, Gabriela Zanfir-Fortuna

1 Article 114 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) – the so-called internal market legal basis – constitutes the primary legal basis of the proposed AIA. Article 16 TFEU – the right to the protection of personal data – also constitutes a legal basis for the future regulation, but only as far as specific rules on the protection of individuals with regard to the processing of their personal data are concerned.