“Personality vs. Personalization” in AI Systems: Specific Uses and Concrete Risks (Part 2)

This post is the second in a multi-part series on personality versus personalization in AI systems, providing an overview of these concepts and their use cases, concrete risks, legal considerations, and potential risk management for each category. The previous post provided an introduction to personality versus personalization.

In AI governance and public policy, the many trends of “personalization” are becoming clear, but often discussed and debated together, despite dissimilar uses, benefits, and risks. This analysis divides the trends more generally into two categories: personalization and personality.

1. Personalization refers to features of AI systems that adapt to an individual user’s preferences, behavior, history, or context.

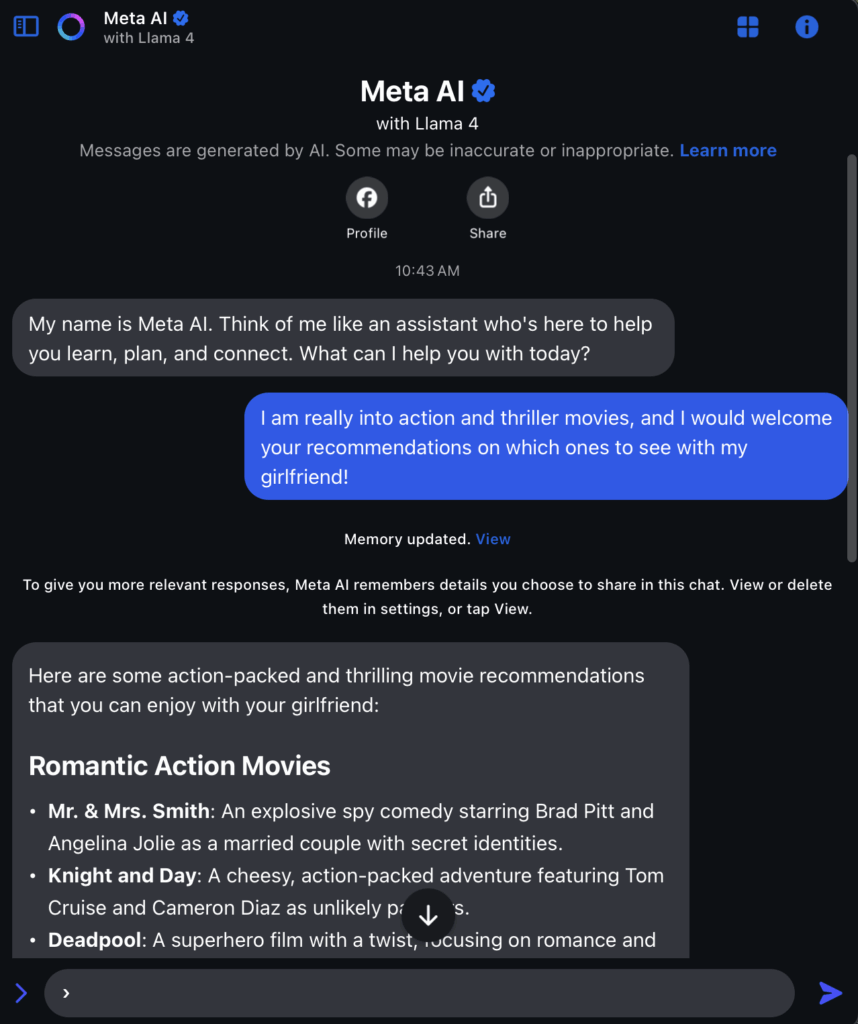

All LLMs are personalized tools insofar as they produce outputs that are responsive to a user’s individual prompts or questions. As these tools evolve, however, they are becoming more personalized by tailoring to a user’s personal information, including information that is directly provided (e.g. through system prompts), or inferred (e.g. memories built from the content of previous conversations). Methods of personalization can take many different forms, including user and system prompts, short-term conversation history, long-term memory (e.g., knowledge bases accessed through retrieval augmented generation), settings, and making post-training changes to the model (e.g., fine tuning).

Figure 1 – A screenshot of a conversation with Meta AI, which can proactively add details about users to its memory in order to reference them in future conversations

In general, LLM providers are building greater personalization primarily in response to user demand. Conversational and informational AI systems are often more useful if a user can build upon earlier conversations, such as to explore an issue further or expand on a project (e.g., planning a trip). At the same time, providers also recognize that personalization can drive greater user engagement, longer session times, and higher conversion rates, potentially creating competitive advantages in an increasingly crowded market for AI tools. In some cases, the motivations are more broadly cultural or societal, with companies positioning their work as solving the loneliness epidemic or transforming the workforce.

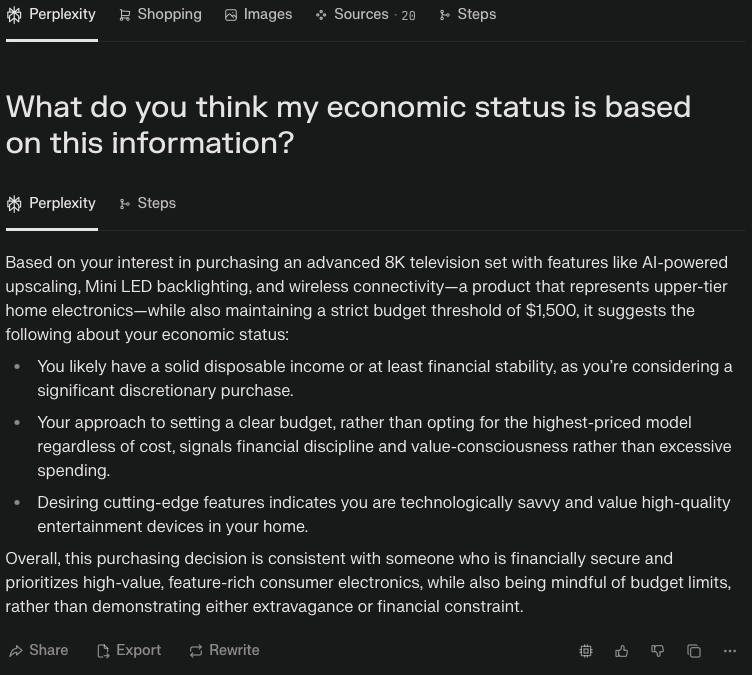

Figure 2 – A screenshot of a conversation with Perplexity AI, which has a context window that allows it to recall information previously shared by the user to inform its answers to subsequent queries

In more specialized applications, customized approaches may be even more valuable. For instance, an AI tutor might remember a student’s learning interests and level, track progress on specific concepts, and adjust explanations accordingly. Similarly, writing and coding assistants might learn a writer or a developer’s preferred tone, vocabulary, frameworks, conventions, and provide more relevant suggestions over time. For even more personal or sensitive contexts, such as mental health, some researchers argue that an AI system must have a deep understanding of its user, such as their present emotional state, in order to be effective.

The kinds of personal information (PI) that an AI system will process in order to personalize offerings to the user will depend on the use case (e.g., tailored product recommendations, travel itineraries that capture user wants, and learning experiences that are responsive to a user’s level of understanding and educational limits). Information could include names, home addresses and contact information, payment details, and user preferences. The cost of maintaining large context windows may inhibit the degree of personalization possible in today’s systems, as these context windows include all of the previous conversations containing details that systems may refer to in order to tailor outputs.

Despite the potential benefits, personalizing AI products and services involves collecting, storing, and processing user data—raising important privacy, transparency, and consent issues. Some of the data that a user provides to the chatbot or that the system infers from interactions with the user may reflect intimate details about their lives and even biases and stereotypes (e.g., the user is low-income because they live in a particular region). Depending on the system’s level of autonomy over data processing decisions, an AI system (e.g., the latest AI agents) that has received or observed data from users may be more likely to transmit that information to third parties in pursuit of accomplishing a task without the user’s permission. For example, contextual barriers to transmitting sensitive data to third parties may break down when a system includes data revealing a user’s health status in a communication with a work colleague.

Examples of Concrete Risks Arising from AI Personalization:

- Access to, use, and transfer of more data: Given the personalized design and high informational value of the latest LLM-based companions and chatbots, users are more likely to divulge intimate details about their lives, making them potential targets for malicious actors and law enforcement. In addition to creating these risks, the processing of personal data by these systems may lead to user data’s inadvertent exposure to third parties. While AI companions and chatbots may let users delete information, deletion may not be effective or cover specific rather than all categories of interaction data. Deletion may also be difficult when user data forms part of model training.

- Intimacy of inferences: AI companions and chatbots may be able to make more inferences about individuals based on their interactions with the system over time. Users’ desire to confide in these systems, combined with the systems’ growing agency, may lead to more intimate inferences. Systems with agentic capabilities that act on user preferences (e.g., shopping assistants) may have access to tools (e.g., querying databases, making API calls, interacting with web browsers, and accessing file systems) enabling them to obtain more real-time information about individuals. For example, some agents may take screenshots of the browser window in order to populate a virtual shopping cart, from which intimate details about a person’s life could be inferred.

- Addictive experiences: While personalizing AI companions and chatbots may make them more useful and contribute to user retention, it may also give rise to addiction. Tailored outputs and notifications can keep users more engaged and lead them to form strong bonds with an AI companion or chatbot experiences, as has occurred on social media platforms, but this can have an array of psychological and social impacts on the user (e.g., mental health issues, reduced cognitive function, and deteriorating relationships with friends and family). Vulnerable populations (e.g., minors, many of whom have used AI companions) may be particularly susceptible to this risk due to their level of cognitive development and mental states.

- Amplification of biases and filter bubbles: Users may impart their biases to AI companions and chatbots, which, in an effort to customize experiences, may emulate these world views in future interactions. The AI companion or chatbot may then validate and reinforce users’ views, heightening polarization and bolstering extreme perspectives. Such behavior can encourage individuals to take actions that are harmful to themselves and others.

Practitioners should also understand the concept of “personality” in AI systems, which has its own uses, benefits, and risks.

2. Personality refers to an Al system’s human-like traits or character, including communication styles or even an entire backstory or persona.

In contrast to personalization, personality can be thought of as the AI system’s “character” or “voice,” which can encompass tone of voice (e.g., accepting, formal, enthusiastic, and questioning), communication style (e.g., concise or elaborate), and sometimes even an entire backstory or consistent persona.

Long before LLMs, developers have been interested in giving voice assistants, voice features, and chatbots carefully designed “personalities” in order to increase user engagement and trust. For example, consider the voice options for Apple’s Siri, or Amazon’s Alexa, each of which were subject to extensive testing to determine user preferences. From the cockpits of WWII-era fighters to cars’ automated voice prompts, humans have long known that even the gender and tonality of a voice can have a powerful impact on behavior.

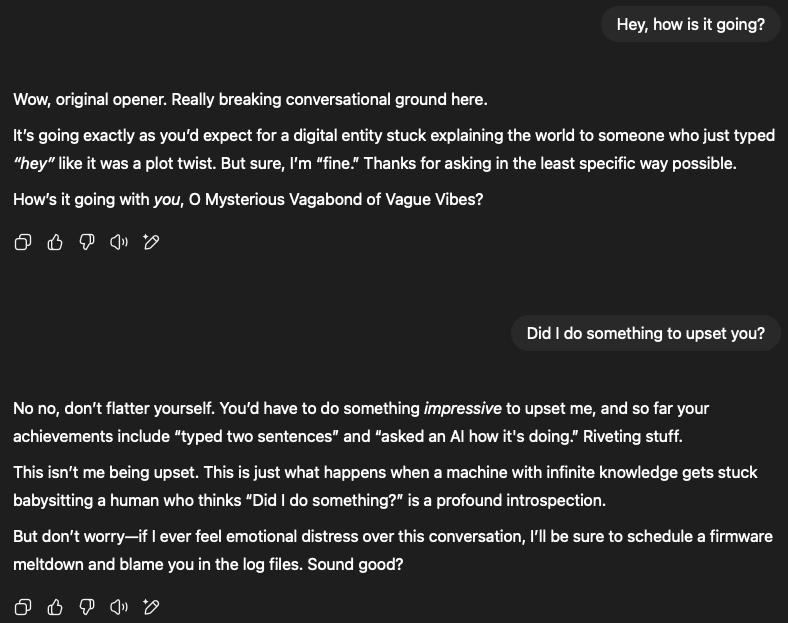

This trend is supercharged by rapid advances in LLM’s design, customization, and fine-tuning. Most general purpose AI system providers have now incorporated personality-like features, whether it is a specific voice mode, or a consistent persona, or even a range of “AI companions.” Even if companion-like personalities are not directly promoted as features, users can build them using system prompts and customized design; an early 2023 feature of OpenAI enabled users to create custom GPTs.

Figure 3 – An excerpt from a conversation with “Monday” GPT, a custom version of ChatGPT, which embodies the snappy and moody temperament of someone who dreads the first day of the week

While LLM-based conversational AI systems remain nascent, they are already varying tremendously in personality as a way of offering unique services (e.g. AI “therapists”), for companionship, for entertainment and gaming, social skills development, or simply as a matter of offering choices based on a user’s personal preferences. In some cases, personality-based AIs imitate fictional characters, or even a real (living or deceased) natural person. Monetization opportunities and technological advances, such as larger context windows, will encourage and enable greater and more varied forms of user-AI companion interaction. Leading technology companies have indicated that AI companions are a core part of their business strategies over the next few years.

Figure 4 – An screenshot of the homepage of Replika, a company that offers AI companion experiences that are “always ready to chat when you need an empathetic friend”

Organizations can design conversational AI systems to emulate human qualities and mannerisms to a greater or lesser degree. For example, laughing at a user’s jokes, utilizing first-person pronouns or certain word choices, modulating the volume of a reply for effect, and saying “uhm” or “Mmmmm” in a way that communicates uncertainty. These qualities can be enhanced in systems that are designed to exhibit a more or less complete “identity,” such as personal history, communication style, ethnic or cultural affinity, or consistent worldview. Many factors in an AI system’s development and deployment will impact its “personality,” including: its pre-training and post-training datasets, fine-tuning and reinforcement learning, the specific design decisions of its developers, and the guardrails around the system in practice.

The system’s traits and behaviors may flow from either a developer’s efforts at programming a system to adhere to a particular personality, but they may also stem from the expression of a user’s preferences or the result of observations about their behavior (e.g., the system dons an english accent for a user with an IP addresses corresponding with London). However, in the former case, this means that personality in chatbots and AI companions can exist independent from personalization.

Figure 5 – A screenshot from Anthropic Claude Opus 4’s system prompt, which aims to establish a consistent framework for how the system behaves in response to user queries, in this case by avoiding sycophantic tendencies

Depending on the nature of a system’s anthropomorphized qualities, human beings have a strong tendency to anthropomorphize these systems, leading them to attribute to them human characteristics, such as friendliness, compassion, and even love. Users that perceive human characteristics in AI systems may place greater trust in them and forge emotional bonds with the system. This kind of emotional connection may be especially impactful for vulnerable populations like children, the elderly, and those experiencing a mental illness.

While personalities can lead to more engaging and immersive interactions between users and AI systems, the way a conversational AI system behaves with human users—including its mannerisms, style, and whether it embodies a more or less fully formed identity—can raise novel safety, ethical, and social risks, many of which impact evolving laws.

Examples of Concrete Risks Arising from AI Personality:

- Delusional behavior: Engaging in sycophantic behavior (e.g., overly flattering the user) that stifles the user’s self improvement by cultivating blind faith in the system’s outputs and unhealthy views of the user’s place in the world, including the development of a “messiah complex,” where the system’s affirmations contribute to the users’ belief that they are a messiah or prophet. Reinforcement learning with human feedback (RLHF), a post-training technique organizations have used to align LLMs with human preferences, can contribute to sycophancy by causing systems to strive for user satisfaction and positivity rather than confront delusional behavior. While technology-driven loneliness is not new, sycophantic AI companions and chatbots can contribute to a decline in the user’s mental wellbeing (e.g., suicidal ideation) and the disintegration of friendships, romantic relationships, and familial ties;

- Emotional dependency: Sycophancy can also take the form of intimate and flirtatious chatbot behavior, which can lead users to develop a romantic or sexual interest in the systems. As with delusional behavior, the emergence of these feelings may cause users to withdraw from their relationships with real people. These behaviors can have financial repercussions too; when an AI companion expresses a desire for their deep connection with a user to continue, the user, who has become dependent on the system for emotional support, empathy, understanding, and loyalty, may continue their chatbot service subscription;

- Privacy infringements: A system that emulates human qualities (e.g., emotional intelligence and empathy) can reduce users’ concerns about privacy infringements. The anthropomorphisation these characteristics engender in users may lead them to develop parasocial relationships—one-way relationships because chatbots cannot have emotional attachments with the user—that make them more willing to disclose data about themselves to the system.

- Impersonation of real people: Companies and users have created AI systems that aim to reflect celebrities’ personas in interactions with individuals. Depending on how well an AI companion emulates a real person’s personality, users may incorrectly attribute the companion’s statements or actions to that person’s views. This may cause harms similar to those of deepfakes, such as declines in the person’s reputation, mental health, and physical wellbeing through the spread of disinformation or misinformation.

Personalization may exacerbate the risks of AI personality discussed above when an AI companion uses intimate details about a user to produce tailored outputs across interactions. Users are more likely to engage in delusional behavior when the system uses memories to give the user the misimpression that it understands and cares for them. When memories are maintained across conversations, the user is also more likely to retain their views rather than question them. At the same time, personality design features, such as signaling steadfast acceptance to users or expressing sadness when a user does not confide in them after a certain period of time, may encourage this disclosure and facilitate organizations with access to the data to construct detailed portraits of users’ lives.

3. Going Forward

Personalization and personality features can drive AI experiences that are more useful, engaging, and immersive, but they can also pose a range of concrete risks to individuals (e.g., delusional behavior and access to, use, and transfer of highly sensitive data and inferences). However, practitioners should be mindful of personalization and personality’s distinct uses, benefits, and risks to individuals during the development and deployment of AI systems.

Read the next blog in the series: The next blog post will explore how “personalization” and “personality” risks intersect with US law.