The “Neural Data” Goldilocks Problem: Defining “Neural Data” in U.S. State Privacy Laws

Co-authored by Chris Victory, FPF Intern

As of halfway through 2025, four U.S. states have enacted laws regarding “neural data” or “neurotechnology data.” These laws, all of which amend existing state privacy laws, signify growing lawmaker interest in regulating what’s being considered a distinct, particularly sensitive kind of data: information about people’s thoughts, feelings, and mental activity. Created in response to the burgeoning neurotechnology industry, neural data laws in the U.S. seek to extend existing protections for the most sensitive of personal data to the newly-conceived legal category of “neural data.”

Each of these laws defines “neural data” in related but distinct ways, raising a number of important questions: just how broad should this new data type be? How can lawmakers draw clear boundaries for a data type that, in theory, could apply to anything that reveals an individual’s mental activity? Is mental privacy actually separate from all other kinds of privacy? This blog post explores how Montana, California, Connecticut, and Colorado define “neural data,” how these varying definitions might apply to real-world scenarios, and some challenges with regulating at the level of neural data.

“Neural” and “neurotechnology” data definitions vary by state.

While just four states (Montana, California, Connecticut, and Colorado) currently have neural data laws on the books, legislation has rapidly expanded over the past couple years. Following the emergence of sophisticated deep learning models and other AI systems, which gave a significant boost to the neurotechnology industry, media and policymaker attention turned to the nascent technology’s privacy, safety, and other ethical considerations. Proposed regulation—both in the U.S. and globally—varies in its approach to neural data, with some strategies creating new “neurorights” or mandating entities minimize the neural data they collect or process.

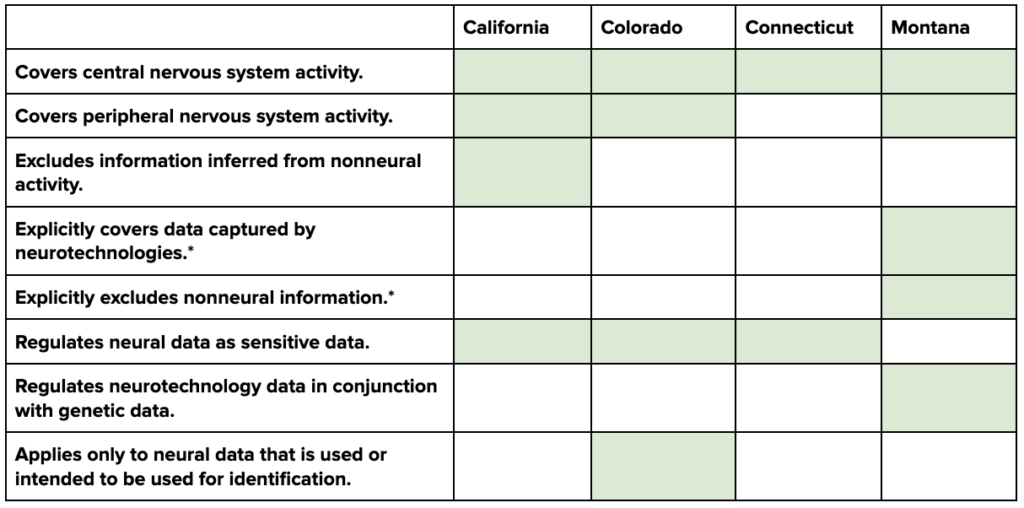

In the U.S., however, laws have coalesced around an approach in which covered entities must treat neural data as “sensitive data” or other data with heightened protections under existing privacy law, above and beyond the protections granted by virtue of being personal information. The requirements that attach to neural data by virtue of being “sensitive” vary by underlying statute, as illustrated in the accompanying comparison chart. In fact, even the way that “neural data” is defined varies by law, placing different data types within scope depending on the state. The following definitions are organized roughly from the broadest conception of neural data to the narrowest.

- California

Generally speaking, the broadest conception of “neural data” in the U.S. laws is California SB 1223, which amends the state’s existing consumer privacy law, the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA), to clarify that “sensitive personal information” includes “neural data.” The law, which went into effect January 1, 2025, defines “neural data” as:

Information that is generated by measuring the activity of a consumer’s central or peripheral nervous system, and that is not inferred from nonneural information.

Notably, however, the CCPA as amended by the California Privacy Rights Act (CPRA) treats “sensitive personal information” no differently than personal information except when it’s used for “the purpose of inferring characteristics about a consumer”—in which case it is subject to heightened protections. As such, the stricter standard for sensitive information will only apply when neural data is collected or processed for making inferences.

- Montana

Montana SB 163 takes a slightly different approach than the other laws in two ways: one, it applies to “neurotechnology data,” an even broader category of data that includes the measurement of neural activity; and two, it amends Montana’s Genetic Information Privacy Act (GIPA) rather than a comprehensive consumer privacy law. The law, which goes into effect October 1, 2025, will define “neurotechnology data” as:

Information that is captured by neurotechologies, is generated by measuring the activity of an individual’s central or peripheral nervous systems, or is data associated with neural activity, which means the activity of neurons or glial cells in the central or peripheral nervous system, and that is not nonneural information. The term does not include nonneural information, which means information about the downstream physical effects of neural activity, including but not limited to pupil dilation, motor activity, and breathing rate.

The law will define “neurotechnology” as:

Devices capable of recording, interpreting, or altering the response of an individual’s central or peripheral nervous system to its internal or external environment and includes mental augmentation, which means improving human cognition and behavior through direct recording or manipulation of neural activity by neurotechnology.

However, the law’s affirmative requirements will only apply to “entities” handling genetic or neurotechnology data, with “entities” defined narrowly—as in the original GIPA—as:

…a partnership, corporation, association, or public or private organization of any character that: (a) offers consumer genetic testing products or services directly to a consumer; or (b) collects, uses, or analyzes genetic data.

While the lawmakers may not have intended to limit its application to consumer genetic testing companies, and may have inadvertently carried over GIPA’s definition of “entities,” the text of the statute may significantly narrow the companies subject to it.

- Connecticut

Similarly, Connecticut SB 1295, most of which goes into effect July 1, 2026, will amend the Connecticut Data Privacy Act to clarify that “sensitive data” includes “neural data,” defined as:

Any information that is generated by measuring the activity of an individual’s central nervous system.

In contrast to other definitions, the Connecticut law will apply only to central nervous system activity, rather than central and peripheral nervous system activity. However, it also does not explicitly exempt inferred data or nonneural information as California and Montana do, respectively.

- Colorado

Colorado HB 24-1058, which went into effect August 7, 2024, amends the Colorado Privacy Act to clarify that “sensitive data” includes “biological data,” which itself includes “neural data.” “Biological data” is defined as:

Data generated by the technological processing, measurement, or analysis of an individual’s biological, genetic, biochemical, physiological, or neural properties, compositions, or activities or of an individual’s body or bodily functions, which data is used or intended to be used, singly or in combination with other personal data, for identification purposes.

The law defines “neural data” as:

Information that is generated by the measurement of the activity of an individual’s central or peripheral nervous systems and that can be processed by or with the assistance of a device.

Notably, “biological data” only applies to such data when used or intended to be used for identification, significantly narrowing the potential scope.

* While only Montana explicitly covers data captured by neurotechnologies, and excludes nonneural information, the other laws may implicitly do so as well.

The Goldilocks Problem: The nature of “neural data” makes it challenging to get the definition just right.

Given that each state law defines neural data differently, there may be significant variance in what kinds of data are covered. Generally, these differences cut across three elements:

- Central vs. peripheral nervous system data: Does the law cover data from both the central and peripheral nervous system, or just the central nervous system?

- Treatment of inferred and nonneural data: Does the law exclude neural data that is inferred from nonneural activity?

- Identification: Does the law exclude neural data that is not used, or intended to be used, for the purpose of identification?

Central vs. peripheral nervous system data

The nervous system comprises the central nervous system (CNS) and the peripheral nervous system (PNS). The CNS—made up of the brain and spinal cord—carries out higher-level functions including thinking, emotions, and coordinating motor activity. The PNS—the network of nerves that connects the CNS to the rest of the body—receives signals from the CNS and transmits this information to the rest of the body instructing it on how to function, and transfers sensory information back to the CNS in a cyclical process. Some of this activity is conscious and deliberate on the part of the individual (voluntary nervous system), while some involves unconscious, involuntary functions like digestion and heart rate (autonomic nervous system).

What this means practically is that the nervous system is involved in just about every human bodily function. Some of this data is undoubtedly particularly sensitive, as it can reveal information about an individual’s health, sexuality, emotions, identity, and more. It may also provide insight into an individual’s “thoughts,” either by accessing brain activity directly or by measuring other bodily data that in effect reveals what the individual is thinking (eg, increased heart and breathing rate at a particular time can reveal stress or arousal). It also means that an incredibly broad swath of data could be considered neural data: the movement of a computer mouse or use of a smartwatch may technically constitute, under certain definitions, neural data.

As such, there is a significant difference between laws that cover both CNS and PNS data, and those that only cover CNS data. Connecticut SB 1295 is the lone current law that applies solely to CNS data, which narrows its scope considerably and likely only covers data collected from tools such as brain-computer interfaces (BCIs), electroencephalogram (EEGs), and other similar devices. However, other data types that would be excluded by virtue of not relating to the CNS could, in theory, provide the same or similar information. For example, signals from the PNS—such as pupillometry (pupil dilation), respiration (breathing patterns), and heart rate—could also indicate the nervous system’s response to stimuli, despite not technically being a direct measurement of the CNS.

Treatment of inferred and nonneural data

Defining “neural data” in a way that covers particular data of concern without being overinclusive is challenging, and lawmakers have added carveouts in an attempt to make their legislation more workable. However, focusing regulation on the nervous system in the first place raises a few potential issues. First, it reinforces neuroessentialism, the idea that the nervous system and neural data are unique and separate from other types of sensitive data; as well as neurohype, the inflation or exaggeration of neurotechnologies’ capabilities. There is not currently—and may never be, as such—a technology for “reading a person’s mind.” What may be possible are tools that measure neural activity to provide clues about what an individual might be thinking or feeling, much the same as measuring their other bodily functions, or even just gaining access to their browsing history. This doesn’t make the data less sensitive, but challenges the idea that “neural data” itself—whether referring to the central, peripheral, or both nervous systems—is the most appropriate level for regulation.

This creates one of two problems for lawmakers. On one hand, defining “neural data” too broadly could create a scenario in which all bodily data is covered. Typing on a keyboard involves neural data, as the central nervous system sends signals through the peripheral nervous system to the hands in order to type. Yet, regulating all data related to typing as sensitive neural data could be unworkable. On the other hand, defining “neural data” too narrowly could result in regulations that don’t actually provide the protections that lawmakers are seeking. For example, if legislation only applies to neural data that is used for identification purposes, it may cover very few situations, as this is not a way that neural data is typically used. Similarly, only covering CNS data, rather than both CNS and PNS data, may be difficult to implement because it’s not clear that it’s possible to truly separate the data from these two systems, as they are interlinked.

One way lawmakers seek to get around the first problem is by narrowing the scope, clarifying that the legislation doesn’t apply to “nonneural information” such as downstream physical bodily effects, or neural data that is “inferred from nonneural information.” For example, Montana SB 163 excludes “nonneural information” such as pupil dilation, motor activity, and breathing rate. However, if the concern is that certain information is particularly sensitive and should be protected (eg, data potentially revealing an individual’s thoughts or feelings), then scoping out this information just because it’s obtained in a different way doesn’t address the underlying issue. For example, if data about an individual’s heart rate, breathing, perspiration, and speech pattern is used to infer their emotional state, this is functionally no different—and potentially even more revealing—than data collected “directly” from the nervous system. Similarly, California SB 1223 carves out data that is “inferred from nonneural information,” leaving open the possibility for the same kind of information to be inferred through other bodily data.

Identification

Another way lawmakers, specifically in Colorado, have sought to avoid an unmanageably broad conception of neural data is to only cover such data when used for identification. Colorado HB 24-1058, which regulates “biological data”—of which “neural data” is one component—only applies when the data “is used or intended to be used, singly or in combination with other personal data, for identification purposes.” Given that neural data, at least currently, is not used for identification, it’s not clear that such a definition would cover many, if any, instances of consumer neural data.

Conclusion

Each of the four U.S. states currently regulating “neural data” defines the term differently, varying around elements such as the treatment of central and peripheral nervous system data, exclusions for inferred or nonneural data, and the use of neural data for identification. As a result, the scope of data covered under each law differs depending on how “neural data” is defined. At the same time, attempting to define “neural data” reveals more fundamental challenges with regulating at the level of nervous system activity. The nervous system is involved in nearly all bodily functions, from innocuous movements to sensitive activities. Legislating around all nervous system activity may render physical technologies unworkable, while certain carveouts may, conversely, scope out information that lawmakers want to protect. While many are concerned about technologies that can “read minds,” such a tool does not currently exist per se, and in many cases nonneural data can reveal the same information. As such, focusing too narrowly on “thoughts” or “brain activity” could exclude some of the most sensitive and intimate personal characteristics that people want to protect. In finding the right balance, lawmakers should be clear about what potential uses or outcomes on which they would like to focus.