New Infographic Highlights XR Technology Data Flows and Privacy Risks

As businesses increasingly develop and adopt extended reality (XR) technologies, including virtual (VR), mixed (MR), and augmented (AR) reality, the urgency to consider potential privacy and data protection risks to users and bystanders grows. Lawmakers, regulators, and other experts are increasingly interested in how XR technologies work, what data protection risks they pose, and what steps can be taken to mitigate these risks.

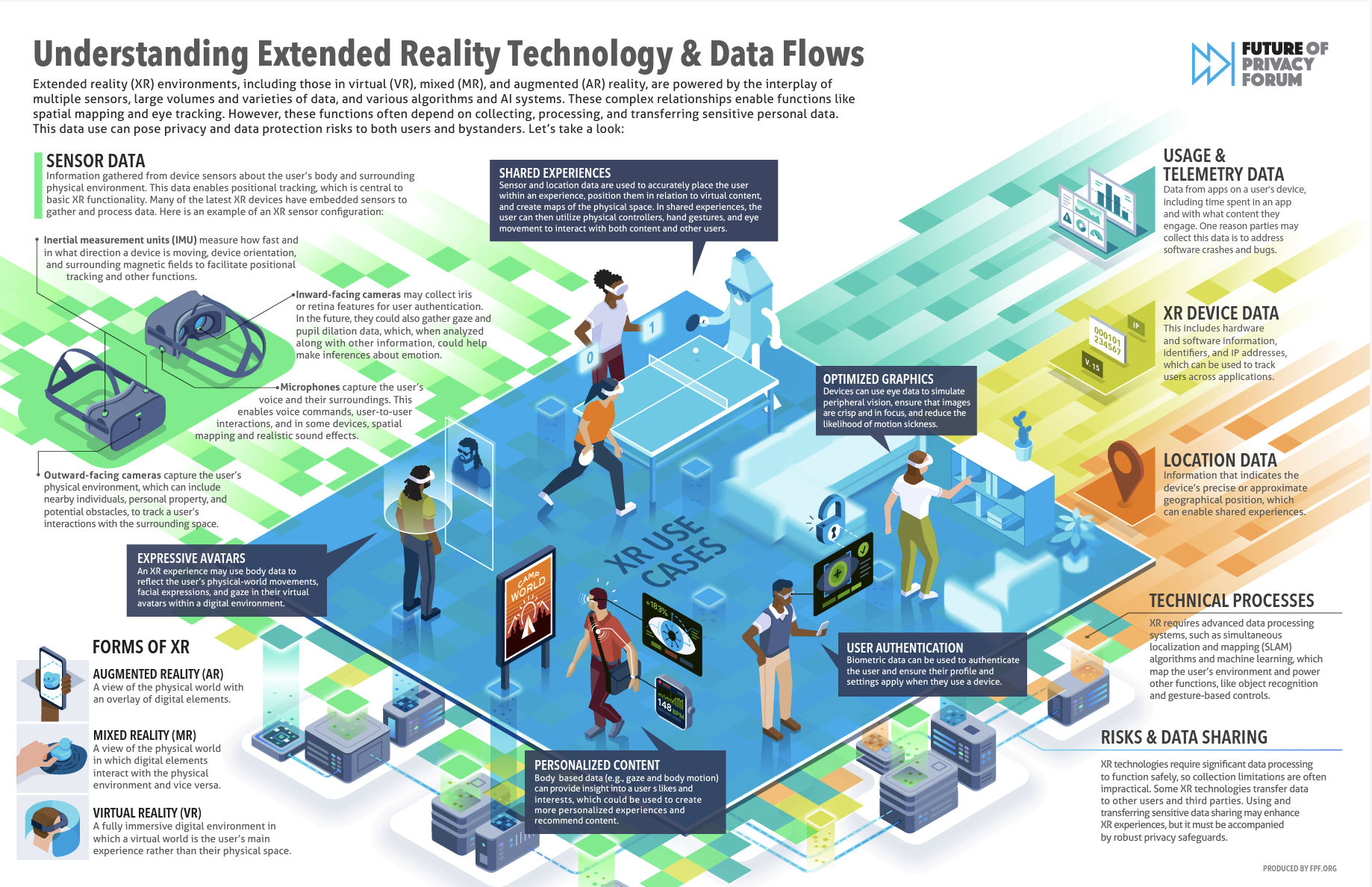

Today, the Future of Privacy Forum (FPF), a global non-profit focused on privacy and data protection, released an infographic visualizing how XR data flows work by exploring several use cases that XR technologies may support. The infographic highlights the kinds of sensors, data types, data processing, and transfers that can enable these use cases.

XR technologies are powered by the interplay of multiple sensors, large volumes and varieties of data, and various algorithms and automated systems, such as machine learning (ML). These highly technical relationships enable use cases like shared experiences and expressive avatars. However, these use cases often depend on information that may qualify as sensitive personal data, and the collection, processing, and transfer of this data may pose privacy and data protection risks to both users and bystanders.

“XR tech often requires information about pupil dilation and gaze in order to function, but organizations could use this info to draw conclusions—whether accurate or not—about the user, such as their sexual orientation, age, gender, race, and health,” said Daniel Berrick, a Policy Counsel at FPF and co-author of the infographic. These data points can inform decisions about the user that can negatively impact their lives, underscoring the importance of use limitations to mitigate risks.

FPF’s analysis shows that sensors that track bodily motions may also undermine user anonymity. While tracking these motions can help map a user’s physical environment, it can also enable digital fingerprinting. This makes it easier for parties to identify users and bystanders while raising de-identification and anonymization concerns. These risks may discourage individuals from fully expressing themselves and participating in certain activities in XR environments due to their concerns about retaliation.

Moreover, FPF found that legal protections for bodily data may depend on privacy regulations’ definitions of biometric data. It is uncertain whether US biometric laws, such as the Illinois Biometric Information Privacy Act (BIPA), apply to XR technologies’ collection of data. “BIPA applies to information based on ‘scans’ of hand or face geometry, retinas or irises, and voiceprints, and does not explicitly cover the collection of behavioral characteristics or eye tracking,” said Jameson Spivack, Senior Policy Analyst, Immersive Technologies at FPF. Spivack was also a co-author of the infographic.

This highlights how existing laws’ protections for biometric data may not extend to every situation involving XR technologies. However, protections may apply to other special categories of data, given XR data’s potential to draw sensitive inferences about individuals.